A sleeve anchor is a pre-assembled expansion fastener. It secures objects to solid materials like concrete, brick, and block. The anchor works by expanding a metal sleeve against the inside of a pre-drilled hole as someone tightens a bolt or nut. This expansion creates a powerful frictional grip. It provides a strong and reliable anchor point for light to heavy-duty applications, ensuring a high load capacity.

The global market for stainless steel sleeve anchors reflects their widespread use. The industry’s growth underscores the demand for reliable fastening solutions.

| Year | Market Size (USD Million) |

|---|---|

| 2024 | 243.66 |

| 2025 | 253.50 |

| 2032 | 591.40 |

Note: The market is projected to grow at a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 11.72% from 2025 to 2032.

Anchor Bolts are critical components in many projects. A custom fasteners manufacturer can even produce custom anchor bolts to meet specific job requirements and ensure minimum holding values are met.

Understanding the Anatomy of Sleeve Anchors

To appreciate how sleeve anchors provide such a secure hold, one must first understand their individual parts. Each component has a distinct role in the expansion mechanism. The anchor is a pre-assembled unit, but its strength comes from the precise interaction of its four core pieces.

The Core Components

The anchor’s design is simple yet highly effective. It consists of a threaded stud, an expansion sleeve, a tapered plug, and a nut and washer assembly. Manufacturers typically produce these components from robust materials to ensure reliability and corrosion resistance.

- Zinc-plated carbon steel

- Type 304 stainless steel

The Threaded Bolt or Stud

The central component is a threaded bolt or stud. This part extends through the entire assembly. It provides the threads necessary for the nut to engage and apply the force that initiates the expansion process.

The Expansion Sleeve

The expansion sleeve is a cylindrical metal tube that surrounds the bolt. This sleeve is often split or scored. These features allow it to flare outward when force is applied from within, forming the primary gripping surface of the anchor.

The Tapered Expander Plug

At the bottom end of the bolt, inside the sleeve, sits a tapered expander plug. This cone-shaped nut is the key to the entire mechanism. Its shape acts as a wedge, forcing the sleeve to expand as it is drawn upward.

The Washer and Nut Assembly

The washer and nut sit at the top of the anchor. The washer distributes the load from the nut across the surface of the object being fastened. Tightening the nut pulls the threaded bolt upward, activating the anchor.

How the Parts Work Together

The genius of the anchor lies in how these simple parts convert rotational force into powerful radial pressure. The process begins the moment an installer tightens the nut.

Mechanical Principle: The anchor’s holding power relies on converting the upward pull on the bolt into an outward push from the sleeve. This creates immense static friction against the walls of the drilled hole.

The Role of the Tapered Plug

When the nut is tightened, it pulls the threaded bolt outward from the hole. This action draws the tapered expander plug up into the expansion sleeve. The plug’s conical shape forces the sides of the sleeve to flare.

How the Sleeve Creates Friction

The outward expansion of the sleeve is the final step in securing the anchor. This action generates the anchor’s holding power through a clear sequence of events.

- Rotating the nut pulls the central bolt outward.

- This pull forces the conical expander plug into the expansion sleeve.

- The sleeve expands radially, pressing firmly against the hole wall.

- This pressure creates significant static friction and local compression of the base material, locking the anchor securely in place.

How the Expansion Mechanism Secures the Anchor

The transformation of a loosely inserted fastener into a load-bearing anchor happens through a three-stage process: insertion, expansion, and frictional locking. Understanding this sequence reveals the simple physics that gives sleeve anchors their impressive strength.

The Initial Insertion Phase

The process begins with a correctly prepared foundation. A clean, accurately sized hole is essential for the anchor to function as designed.

Placing the Anchor in the Hole

An installer places the pre-assembled anchor unit through the fixture and into the pre-drilled hole in the concrete or masonry. The anchor should slide in with minimal resistance. A light tap from a hammer may be necessary to seat it fully until the washer rests flush against the surface of the material being fastened.

Activating the Expansion

With the anchor in position, the next step is to activate the expansion mechanism. This is achieved by applying rotational force to the nut or bolt head.

The Action of Tightening the Nut

Turning the nut with a wrench initiates a precise mechanical sequence. This simple rotational action is what generates the anchor’s immense holding power. The activation follows a clear order of events:

- Tightening the nut pulls the internal threaded bolt or stud outward, toward the installer.

- This action draws the tapered cone-shaped plug at the bottom of the anchor up into the expansion sleeve.

- The upward movement of the cone forces the surrounding sleeve to expand radially outward.

Forcing the Sleeve to Flare Outward

The core of the mechanism is the interaction between the tapered plug and the expansion sleeve. As the cone-shaped plug is drawn upward, its increasing diameter acts like a wedge. This forces the splits or seams in the sleeve to open, causing the entire length of the sleeve to flare. This creates a full 360-degree contact area between the anchor and the wall of the hole.

Achieving a Secure Frictional Hold

The final stage is the creation of a powerful, locked connection. The outward pressure from the expanded sleeve generates tremendous friction against the base material, creating a secure hold that resists pull-out and shear forces.

Pressing Against the Base Material

The anchor’s locking action relies on two primary physics principles working in tandem:

- Friction-Based Grip: The immense outward force exerted by the expanding sleeve creates a high-friction bond with the interior walls of the hole. This friction is the main force that prevents the anchor from being pulled out under load.

- Keying or Undercutting: The expanding metal sleeve also presses into the small imperfections and pores of the concrete or brick. This creates a mechanical interlock, where the anchor is physically “keyed” into the base material, further increasing its resistance to movement.

The Importance of Torque

Achieving the manufacturer’s specified load capacity depends directly on applying the correct amount of rotational force, known as installation torque. Under-tightening prevents the sleeve from expanding fully, resulting in a weak hold. Over-tightening can damage the anchor’s threads or even crack the base material.

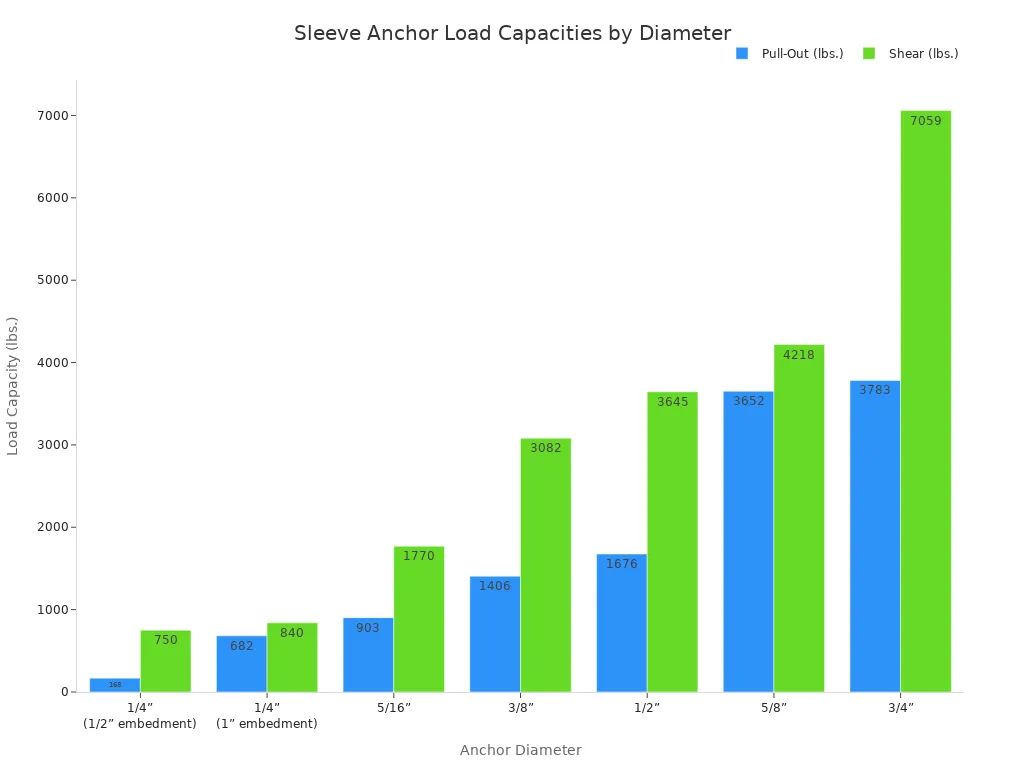

The anchor’s diameter and embedment depth directly influence its ultimate strength. As the diameter increases, so does its capacity to handle both pull-out (tension) and shear (sideways) loads.

| Diameter | Pull-Out (lbs.) | Shear (lbs.) |

|---|---|---|

| 1/4” (1” embedment) | 682 | 840 |

| 5/16” | 903 | 1770 |

| 3/8” | 1406 | 3082 |

| 1/2” | 1676 | 3645 |

| 5/8” | 3652 | 4218 |

| 3/4” | 3783 | 7059 |

Safety First: The values above represent ultimate failure points in 2000 PSI concrete. For safe working loads, engineers apply a safety factor, typically 4:1. This means the intended load should not exceed 25% of the anchor’s ultimate capacity.

The relationship between anchor size and strength is clear. Larger diameters provide a greater surface area for friction and can withstand significantly higher forces.

Following the manufacturer’s torque specifications ensures that these sleeve anchors perform reliably and safely.

Tools and Materials Needed for Installation

A successful sleeve anchor installation depends on using the correct tools and materials. Proper preparation and the right equipment ensure the anchor achieves its maximum holding power and provides a safe, reliable connection. Gathering these items before starting the project streamlines the entire process.

Essential Tools

An installer needs a specific set of tools to work with masonry and properly set the anchor. Each tool performs a critical function, from drilling the hole to applying the final torque.

Hammer Drill or Rotary Hammer

A standard drill is not sufficient for concrete or brick. An installer must use a hammer drill or a more powerful rotary hammer. These tools combine rotation with a rapid hammering action. This percussive force pulverizes the masonry, allowing the drill bit to advance efficiently and create a clean, uniform hole.

Carbide-Tipped Masonry Drill Bit

The drill bit must be specifically designed for masonry and feature a carbide tip. Carbide is an extremely hard material that can withstand the abrasive nature of concrete. The bit’s diameter must exactly match the diameter of the sleeve anchor. Using an incorrect size will compromise the anchor’s performance.

Wrench or Socket Set

A wrench is necessary to tighten the nut and activate the anchor’s expansion mechanism. An adjustable wrench can work for various anchor sizes. However, a socket set with a torque wrench is the professional choice. It allows the installer to apply the precise amount of torque specified by the manufacturer, preventing under-tightening or over-tightening.

Wire Brush and Compressed Air/Blower

Cleaning the drilled hole is a non-negotiable step for a secure installation.

- Wire Brush: A narrow wire brush, matched to the hole’s diameter, scrubs the interior walls. This action loosens concrete dust and debris created during drilling.

- Compressed Air/Blower: After brushing, a blast of compressed air or a manual blower removes all loose particles from the hole.

Critical Step: A clean hole ensures the expansion sleeve makes direct contact with the solid base material. Debris can act like tiny ball bearings, reducing friction and severely weakening the anchor’s grip.

Safety Equipment

Working with masonry and power tools presents inherent risks. Using the proper personal protective equipment (PPE) is essential for preventing injury.

Safety Glasses

Drilling into concrete, brick, or block creates flying dust and sharp particles. High-quality, wrap-around safety glasses or goggles are mandatory. They protect the installer’s eyes from impact and irritation, which is a primary safety concern during any installation.

Gloves

Heavy-duty work gloves serve multiple protective functions. They shield the hands from scrapes and cuts from the rough masonry surface and the anchor’s metal threads. Gloves also help absorb some of the vibration from the hammer drill, reducing fatigue.

Step-by-Step Installation Guide for Sleeve Anchors

A successful and secure connection depends entirely on the correct installation of sleeve anchors. This step-by-step installation guide breaks down the procedure into clear, manageable actions. Following this sequence ensures the anchor achieves its full load-bearing capacity and provides a safe, lasting hold. The entire installation process is straightforward when an installer uses the right tools and techniques.

Step 1: Drill the Hole

The first and most critical phase is creating a precise hole in the base material. The location and dimensions of this hole form the foundation for the anchor’s performance. To prevent the interaction of forces between anchors, installers should maintain a minimum spacing of ten anchor diameters between each anchor. When drilling near an unsupported edge, a minimum distance of five anchor diameters is the professional standard.

Match Drill Bit to Anchor Diameter

An installer must select a carbide-tipped masonry drill bit. The diameter of this bit must exactly match the diameter of the anchor. For example, a 3/8” anchor requires a 3/8” drill bit. Using a bit that is too small will prevent the anchor from fitting. A bit that is too large will create a loose hole where the sleeve cannot expand enough to create the necessary friction.

Drill to the Required Depth

The hole must be drilled to a specific depth to ensure proper installation. The required hole depth depends on the anchor’s length and the thickness of the material being fastened. A simple calculation determines the minimum hole depth:

Hole Depth = Thickness of Fixture + Minimum Embedment Depth

The anchor’s packaging or technical data sheet specifies the minimum embedment depth. This is the shortest length of the anchor that must be embedded in the base material to achieve its rated strength. The hole should be drilled slightly deeper than this calculated value to leave room for any small amount of dust that cannot be removed.

Step 2: Clean the Hole

A clean hole is absolutely essential for a strong connection. Any dust or debris left inside will interfere with the expansion mechanism and severely compromise the anchor’s holding power.

Brush Away Dust and Debris

After drilling, an installer uses a narrow wire brush to scrub the interior walls of the hole. The brush’s diameter should match the hole’s diameter to ensure it makes full contact. This vigorous scrubbing action loosens all the fine concrete or brick dust that clings to the surface.

Blow Out Remaining Particles

Following the brushing, the installer must remove all loose particles. This is best accomplished with a blast of compressed air. A manual hand pump or blower is also an effective alternative. The installer repeats the brushing and blowing process until no more dust emerges from the hole. A clean hole allows the expansion sleeve to press directly against the solid base material.

Step 3: Insert the Anchor

With a clean, correctly sized hole, the anchor is ready for placement. The anchor is a pre-assembled unit, so an installer should not take it apart before insertion.

Tap the Anchor into Place

The installer first positions the object to be fastened over the hole. Then, they insert the anchor through the fixture and into the hole. The anchor should slide in smoothly. If it meets slight resistance, a light tap with a hammer on the nut will help seat it completely.

Ensure the Washer is Flush

The anchor is properly seated when the washer rests flat and snug against the surface of the fixture. The nut and the end of the threaded stud will protrude above the washer. This position confirms the anchor is at the correct depth and ready for the final tightening and expansion phase.

Step 4: Set the Anchor and Secure the Fixture

This final step is where the mechanical magic happens. The installer transforms the loosely placed fastener into a permanent, load-bearing anchor. Proper execution in this phase is critical for achieving the anchor’s full strength and ensuring a safe installation.

Position Your Fixture

Before setting the anchor, the installer confirms the fixture is correctly aligned over the drilled hole. The object being mounted, whether it’s a handrail bracket or a piece of machinery, should sit flat and stable against the base material. The anchor, already inserted through the fixture, is now ready for activation.

Tighten the Nut to Expand the Sleeve

Tightening the nut is the action that expands the sleeve and locks the anchor in place. The goal is not simply to make the nut feel tight; it is to apply a specific amount of force to achieve the required tension. Industry standards, such as those from the AISC Steel Construction Manual, require that bolts reach a “snug-tight” condition before final tightening. This means the nut is turned until it makes firm contact with the washer and fixture, bringing all surfaces into direct contact.

From this snug-tight point, professionals use one of several recognized methods to apply the final tension:

- Turn-of-the-Nut Method: After snug-tightening, the installer rotates the nut a specific, predetermined amount (e.g., one-third of a turn). This method, highlighted by the RCSC Specification, achieves the required tension by controlling the bolt’s elongation without needing to measure the load directly.

- Calibrated Wrench Method: This technique uses a calibrated torque wrench to apply a precise amount of rotational force. The installer tightens the nut until the wrench indicates that the specified installation torque value has been reached. This is the most common method for achieving accurate tension in sleeve anchors.

- Direct Tension Indicator (DTI) Method: This advanced method involves using a special washer with small protrusions. As the installer tightens the nut, the protrusions compress. The installer visually inspects the gap, and when it closes to a specified amount, the correct tension has been achieved.

Industry Insight: Professional standards from bodies like AASHTO and AISC provide detailed guidelines for bolt tension. A key principle is achieving a minimum tension, often 70% of the bolt’s ultimate strength, to create a rigid connection. This ensures the joint can resist vibration and load changes without loosening over time.

Applying the correct tension is the final, critical action. It draws the cone into the sleeve, forces the 360-degree expansion, and generates the immense frictional force that gives the anchor its powerful grip. This controlled process ensures the connection is both strong and reliable.

Common Applications for Sleeve Anchors

An installer can use sleeve anchors in a wide range of applications. Their versatility makes them a popular choice for fastening objects to various masonry surfaces. The anchor’s expansion mechanism works reliably in both dense and hollow base materials. This adaptability allows for their use in everything from light-duty residential projects to heavy-duty commercial installations.

Suitable Base Materials

Sleeve anchors are designed specifically for masonry. Their performance, however, can vary depending on the density and integrity of the base material. An installer must consider the material’s properties to ensure a secure connection.

Solid Concrete

Solid concrete is the ideal base material for sleeve anchors. Its high compressive strength provides a robust and uniform surface for the expansion sleeve to grip. In structural applications, building codes regulate the use of post-installed anchors.

- The California Building Code (Chapter 19A) requires specific testing for post-installed anchors to verify their performance.

- Industry standards like ACI 318 and ACI 355.2 provide design and qualification requirements for mechanical anchors in concrete. These codes ensure that only anchors proven through independent testing are used for critical connections.

Brick and Masonry

Installers frequently use sleeve anchors in solid brick and other dense masonry walls. The anchor’s 360-degree expansion creates a firm grip within the brick. It is crucial to drill into the solid part of the brick, not the mortar joints. Mortar is much weaker and will not provide adequate holding power.

Concrete Block (CMU)

Concrete Masonry Units (CMUs), or concrete blocks, are also suitable for these fasteners. An installer can place the anchor in either the solid sections or the hollow cells of the block. When anchoring in a hollow section, a longer sleeve anchor is necessary. The longer sleeve ensures the expansion occurs deeper inside the block, spanning the hollow cavity and engaging with the block’s inner and outer walls for a secure hold.

Typical Uses

The reliability and straightforward installation of sleeve anchors make them a go-to solution for many common fastening tasks. They are capable of supporting both static and dynamic loads across various settings.

Securing Handrails and Guardrails

Safety is paramount when installing handrails and guardrails. Installers use sleeve anchors to securely fasten the mounting flanges of these fixtures to concrete steps, walkways, and block walls. The anchor’s ability to resist both pull-out and shear forces ensures the railing remains stable and safe for public use. The anchor’s load capacity is a critical factor in these life-safety applications.

Mounting Brackets and Shelving

For both residential and commercial storage, these anchors provide a strong foundation for mounting heavy-duty brackets and shelving systems. An installer can use them to attach wall-mounted shelves in garages, warehouses, and workshops. The anchors ensure the shelving can support significant weight without pulling away from the wall, making them ideal for storing tools, equipment, and inventory.

Fastening Machinery to Floors

In industrial environments, securing machinery to concrete floors is essential to prevent movement and vibration. Sleeve anchors are an excellent choice for fastening the bases of light to medium-duty equipment. They provide the necessary strength to hold machinery in place, ensuring operational stability and workplace safety. For heavy loads, engineers select larger diameter anchors to meet the required minimum holding values and prevent equipment shifting during operation.

Choosing the Right Type of Sleeve Anchor

An installer’s choice of sleeve anchor head style directly impacts the project’s final appearance and functionality. While all sleeve anchors operate on the same expansion principle, manufacturers offer different head types to suit specific application requirements. Selecting the correct head ensures the fastener not only provides a secure connection but also meets the aesthetic and practical needs of the installation. From standard utility fastening to decorative architectural fixtures, there is a head style designed for the job.

Hex Nut Head

The hex nut head is the most common and versatile type of sleeve anchor. Its design is purely functional, prioritizing ease of installation and high clamping force over aesthetics.

For Standard Applications

An installer uses a standard wrench or socket to tighten the external hex nut. This design allows for the application of precise torque, making it the go-to choice for a majority of light to heavy-duty fastening jobs. Its widespread use in securing structural elements, machinery, and utility brackets makes it the workhorse of the sleeve anchor family. The exposed nut and washer assembly provides a clear visual confirmation of a secure connection, which is critical in industrial and construction settings.

Flat Head (Countersunk)

The flat head sleeve anchor, also known as a countersunk anchor, is designed for applications where a smooth, flush surface is essential. The head is shaped like a cone, allowing it to sit level with or slightly below the surface of the fixture.

For a Flush Finish

This anchor type is the preferred choice when the fastener head must not protrude. A flush surface prevents snagging and provides a clean, finished look. To install it, an installer must create a countersunk hole in the material being fastened.

- Flush Surface Requirement: Installers select flat-headed sleeve anchors when the anchor’s head must be flush with the surface of the fastened material.

- Light to Medium-Duty Fastening: These anchors are well-suited for applications requiring light to medium-duty fastening strength.

- Specific Applications: Common uses include attaching door frames to block walls and securing stair treads to concrete steps, where a raised head would be a trip hazard.

Round Head

The round head sleeve anchor offers a compromise between the utility of a hex head and the low profile of a flat head. It features a smooth, domed head that provides a more finished look than an exposed nut.

For a Finished Appearance

Installers choose round head configurations to match aesthetic preferences, especially in visible locations. The clean, unobtrusive appearance makes this style a popular option for public-facing and architectural installations.

- Round head sleeve anchors are used for architectural fixtures where appearance is a key consideration.

- These options are available for various aesthetic applications, providing a more decorative and less industrial look than a standard hex nut. The smooth dome is also easier to clean and less likely to snag clothing or equipment.

Acorn Nut

The acorn nut sleeve anchor represents the fusion of structural integrity and aesthetic refinement. This anchor type provides the same reliable expansion mechanism as its utilitarian counterparts. Its defining feature is a domed cap nut that conceals the end of the threaded stud. This design choice elevates the fastener from a simple component to a deliberate design element. Professionals select this anchor when the final appearance of the connection is as important as its strength. The acorn nut offers a clean, safe, and finished look that standard hex nuts cannot match.

For Decorative Purposes

An installer chooses an acorn nut sleeve anchor for projects demanding a high-end, polished finish. The rounded head covers sharp threads, preventing snags and creating a smooth, touch-safe surface. This makes it an ideal solution for architectural and public-facing installations where every detail contributes to the overall design. The choice of head style often depends on the project’s specific aesthetic goals.

| Head Type | What It Looks Like | Best Use |

|---|---|---|

| Acorn Head | Rounded, dome-shaped head | Decorative jobs where style is important |

The acorn head’s rounded, dome-shaped profile provides a distinctly polished appearance. This characteristic makes it the premier choice for decorative projects where aesthetic style is a key consideration. Installers use these anchors for a variety of high-visibility applications:

- Architectural Metalwork: Securing ornamental railings, decorative grilles, and custom signage.

- High-End Retail Fixtures: Mounting display cases, shelving, and boutique fixtures where hardware is part of the brand’s image.

- Public Art and Monuments: Fastening plaques, sculptures, and park benches where the hardware should be unobtrusive and elegant.

- Custom Furniture: Attaching built-in furniture pieces to masonry walls in upscale residential or commercial interiors.

Pro Tip: 💡 The installation of an acorn nut sleeve anchor requires a two-step tightening process. An installer first uses a standard hex nut to tighten the anchor to the specified torque value. This ensures the sleeve expands correctly and achieves its full holding power. After setting the anchor, the installer removes the temporary hex nut and replaces it with the permanent acorn nut for the final, decorative finish.

This method guarantees that the connection is structurally sound without compromising the acorn nut’s pristine surface. This anchor provides a sophisticated solution for designers and builders who refuse to compromise on either performance or appearance.

Troubleshooting When Installing Sleeve Anchors

Even with careful preparation, installers can encounter issues when installing sleeve anchors. Most problems trace back to a few common errors in the drilling or cleaning phase. Understanding how to diagnose and correct these issues ensures a secure and reliable installation.

Problem: The Anchor Spins in the Hole

An anchor that spins freely in its hole is a clear sign that the expansion mechanism has not engaged. The sleeve is not creating enough friction against the base material to allow the nut to tighten and draw the cone upward.

Check for an Oversized Hole

The most frequent cause of a spinning anchor is a hole that is too large. This issue can arise from several mistakes during the drilling process.

- Using a drill bit with the wrong diameter.

- Failing to set a hammer drill to its proper hammer-and-rotation mode.

- Using a worn or low-quality drill bit that does not meet ANSI standards for hole tolerance.

A hole that is even a millimeter oversized can prevent the anchor from gripping. The collar beneath the anchor’s head is designed for a specific hole size. A larger opening allows the entire unit to move, preventing the initial bite needed for expansion. The best solution is to abandon the hole and drill a new one correctly.

Ensure the Hole is Clean

While less common for spinning, excessive dust can sometimes lubricate the hole. If the hole size is correct, a final cleaning with a wire brush and compressed air may provide the friction needed for the sleeve to engage.

Problem: The Anchor Won’t Go in All the Way

An anchor that gets stuck before it is fully seated points to an obstruction or an improperly prepared hole. An installer should never use excessive force to hammer an anchor into place.

Verify Hole Depth

The drilled hole must be deep enough to accommodate both the anchor and any residual dust. A common error is drilling a hole that is exactly the length of the anchor.

Pro Tip: 💡 Always drill the hole at least 1/2 inch deeper than the required anchor embedment depth. An installer can mark the correct depth on the drill bit with a piece of tape to serve as a visual guide, ensuring sufficient clearance.

Check for Debris Obstruction

Concrete dust and debris are the most common obstructions. If the hole is not cleaned thoroughly, a dense plug of dust can form at the bottom, blocking the anchor.

- Remove the anchor from the hole.

- Use a wire brush and compressed air or a vacuum to remove all particles.

- Repeat the cleaning process until no more dust emerges. A perfectly clean hole is critical for proper installation and achieving the anchor’s specified holding values.

Problem: The Nut is Tight, but the Fixture is Loose

This is a critical failure that indicates the anchor is not secure, even though the nut feels tight. The fixture is unsafe and cannot support any load. This problem points to incorrect torque or a compromised base material.

Confirm Correct Tightening Torque

The feeling of “tightness” can be misleading. If an installer under-tightens the nut, the sleeve will not expand enough to create a secure grip. Conversely, over-tightening can strip the anchor’s threads or damage the cone, rendering it useless. Using a calibrated torque wrench to apply the manufacturer’s specified torque is the only way to guarantee proper expansion.

Inspect for Base Material Failure

If the torque is correct but the fixture is still loose, the base material itself has likely failed. The outward pressure from the expanding sleeve may have crushed weak or porous concrete, brick, or block. The anchor is essentially sitting in a pocket of crumbled material with nothing solid to grip. In this scenario, the only safe solution is to remove the failed anchor and install a new one in a different location with solid base material.

Sleeve anchors offer a robust fastening solution for masonry, relying on a simple expansion mechanism. The success and safety of any project, however, depend entirely on proper installation. Following the step-by-step guide helps installers avoid common mistakes and create a secure anchor point for a wide variety of projects.

Key Takeaways for a Safe Installation:

- Always use the correct diameter drill bit to prevent the anchor from spinning.

- Wear safety glasses and a dust mask to protect against harmful silica dust.

- Ensure the anchor does not expand into a hollow section of block or brick.

FAQ

Can an installer reuse a sleeve anchor?

No, an installer cannot reuse a sleeve anchor. The expansion sleeve deforms permanently during the initial installation. Reusing a deformed anchor severely compromises its holding power and creates an unsafe connection. Professionals always use a new anchor for every application.

What is the difference between a sleeve anchor and a wedge anchor?

A sleeve anchor expands along its body, making it ideal for brick and block. A wedge anchor expands only at its base, offering superior strength in solid concrete. The choice depends entirely on the base material’s properties.

How close to an edge can an installer place a sleeve anchor?

An installer must maintain a minimum distance of five anchor diameters from an unsupported edge. For example, a 1/2″ anchor requires at least 2.5 inches of clearance. This practice prevents the concrete from cracking under pressure.

Do sleeve anchors work in hollow block?

Yes, they are effective in hollow concrete block (CMU). An installer must select a longer anchor. The extended sleeve length ensures it spans the void and expands against the block’s inner and outer walls, creating a secure hold.

What happens if an installer over-tightens a sleeve anchor?

Over-tightening is a critical error. It can strip the anchor’s threads or fracture the base material, causing a complete failure. Using a calibrated torque wrench to meet the manufacturer’s specification is the only way to ensure a proper installation.

How does an installer remove a sleeve anchor?

An installer can remove the fastened object by unthreading the nut. The anchor body, however, remains permanently set in the concrete. The best options are:

- Drive the anchor deeper into the hole.

- Cut the anchor flush with the surface.

- Patch the hole afterward.

Are sleeve anchors waterproof?

The anchor itself is not a waterproofing element. For outdoor or wet applications, an installer should use a stainless steel anchor to resist corrosion. Applying a bead of silicone sealant around the fixture can help minimize water intrusion.