This glossary offers clear definitions for essential terms in industrial bolting. It covers everything from basic flange bolts to the specifics of bolt casting. A custom fasteners manufacturer often produces a wide array of custom fasteners for specialized applications. The proper Flange Bolt selection is critical for system integrity.

Note: This guide serves as a quick and reliable reference. Engineers, technicians, and procurement specialists will find it invaluable for daily tasks and project planning.

Glossary Terms: A – C

This section covers foundational terms from A to C, detailing critical materials, surface treatments, and the governing bodies that standardize them.

Alloy Steel

Alloy steel is a type of steel that contains specific quantities of alloying elements in addition to carbon. Manufacturers add elements like manganese, nickel, chromium, molybdenum, and vanadium to the steel. These additions enhance its mechanical properties, such as hardness, strength, toughness, and resistance to corrosion and high temperatures.

In flange applications, specific grades of alloy steel are chosen based on the operational environment. For high-temperature and high-pressure services, chromium-molybdenum (Chrome-Moly) steels are common. Grades like B7 and B16 are industry workhorses, each suited for different temperature ranges.

| Grade | Typical Temperature Range | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| B7 | Up to ~840°F (450°C) | General refinery and power piping, high-pressure steam lines, and oil and gas gathering pipelines. A standard for ASME Class 150 to 1500 flanges. |

| B16 | Up to ~1100°F (593°C) | Superheated steam systems, refinery heaters, reformer units, and critical high-temperature assemblies. Often used in ASME Class 900 to 2500 systems. |

Anodizing

Anodizing is an electrochemical process that converts the metal surface into a decorative, durable, and corrosion-resistant anodic oxide finish. Technicians submerge a metal part, typically aluminum, into an acid electrolyte bath and pass an electric current through it. This process grows an oxide layer directly from the underlying metal, making it incredibly durable.

While not common for steel bolts, anodizing is frequently applied to fasteners made from non-ferrous metals like aluminum or titanium. Its primary benefits include:

- Corrosion Resistance: The oxide layer provides a robust barrier against environmental damage.

- Wear Resistance: The hardened surface withstands abrasion better than the raw metal.

- Aesthetic Finish: The process allows for the addition of color for identification or appearance.

ASME (American Society of Mechanical Engineers)

ASME is a professional organization that develops and maintains codes and standards for mechanical devices and systems. These standards ensure safety, reliability, and operational efficiency across numerous industries. For bolted flange connections, adherence to ASME standards is critical for ensuring components fit together correctly and can withstand specified pressures and temperatures.

Note: Compliance with ASME codes is often a regulatory requirement. It guarantees that fasteners and flanges from different manufacturers are interchangeable and meet stringent safety criteria for high-pressure systems.

Several key ASME standards govern the dimensions and specifications of flanges and bolts:

- ASME B16.5: This standard covers dimensions for pipe flanges and flanged fittings for sizes from NPS ½” through NPS 24″ in pressure classes 150 to 2500.

- ASME B18.2.1: This document specifies the dimensional requirements for square, hex, and heavy hex bolts and screws. It ensures that bolt heads, shank lengths, and thread profiles meet universal expectations for fit and function.

ASTM (American Society for Testing and Materials)

ASTM International, formerly known as the American Society for Testing and Materials, is a global organization that develops and publishes voluntary consensus technical standards. These standards cover a vast range of materials, products, systems, and services. In the world of fasteners, ASTM specifications are paramount. They define the precise chemical composition, mechanical properties, heat treatment, and testing requirements for bolts, nuts, and studs.

Following an ASTM standard ensures that a fastener will perform as expected under specific service conditions. For example, ASTM standards differentiate materials suitable for high-temperature versus low-temperature environments.

ASTM A193 vs. ASTM A320: A Key Distinction ASTM A193 is the standard for alloy and stainless steel bolting intended for high-temperature service. In contrast, ASTM A320 specifies materials for low-temperature service. The primary difference lies in toughness testing. A320 Grade L7 bolts, for instance, must undergo a Charpy V-Notch impact test at -150°F (-101°C) to prove they will not become brittle in cryogenic conditions. A193 Grade B7 bolts do not have this mandatory low-temperature requirement.

Axial Tension

Axial tension is the stretching force, or preload, generated along the length of a bolt as it is tightened. This tension is the critical force that creates the “clamp load,” which holds the flange joint together and resists external forces trying to pull it apart. Achieving the correct amount of axial tension is the primary goal of any bolting procedure.

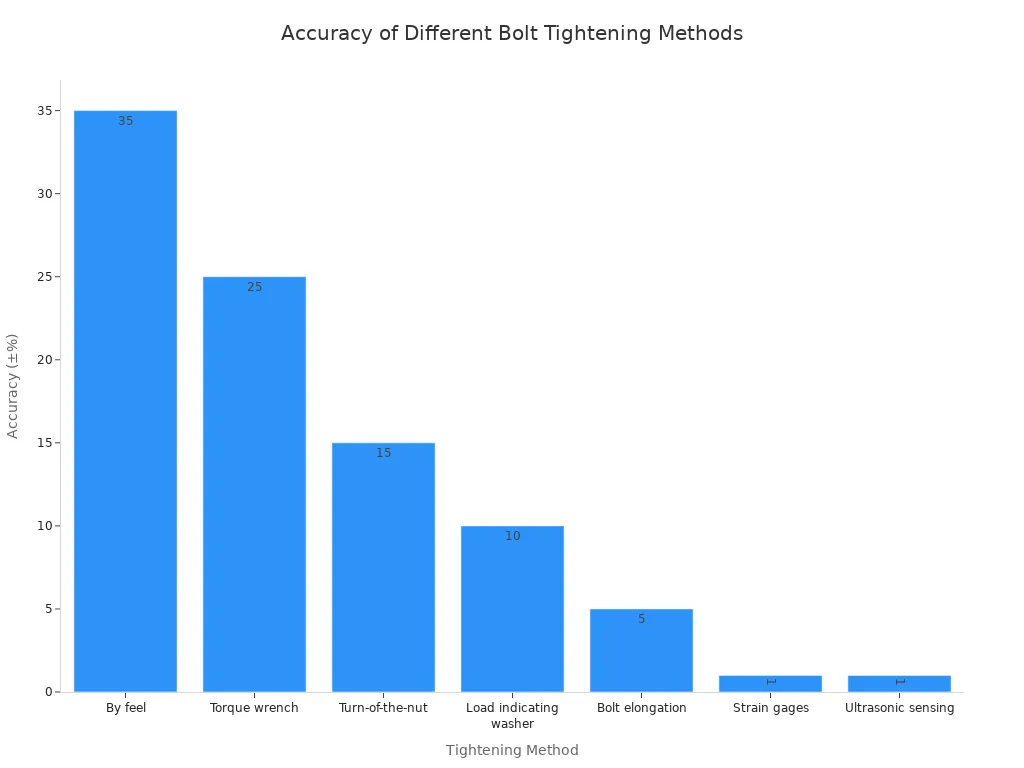

Technicians most commonly apply torque to a nut to generate this tension. However, the relationship is not direct due to friction. The formula T = KT * d * F illustrates this, where T is torque, KT is the nut factor (accounting for friction), d is the bolt diameter, and F is the axial tension. Factors like lubrication, coatings, surface finish, and contaminants can significantly alter the nut factor, affecting the final preload. The accuracy of achieving the target tension varies widely by method.

Bearing Surface

The bearing surface is the area of contact between the underside of the bolt head or nut and the surface of the flange or washer. This surface is responsible for transferring the bolt’s preload (axial tension) into clamping force on the joint. The condition of this surface is critical for the integrity and safety of the entire bolted connection.

Friction at the bearing surface consumes a significant portion of the applied torque—often around 50%. The characteristics of this friction have a profound impact on the joint:

- High Friction: If the friction coefficient is too high (e.g., due to a rough or unlubricated surface), more torque is wasted overcoming it. This can result in an axial force that is too low, leaving the joint under-clamped and prone to loosening.

- Low Friction: If the friction coefficient is too low, the same amount of torque can generate an axial force that surpasses the bolt’s material strength, risking fastener failure or damage to the flange surface.

Therefore, controlling the bearing surface’s condition through proper cleaning, lubrication, and the use of hardened washers is essential for achieving a predictable and safe clamp load.

Bevel

A bevel is an angled or chamfered edge on a fastener or flange. On stud bolts, manufacturers often apply a bevel to the ends. This slight angle makes it easier to start threading a nut onto the bolt. The bevel guides the nut smoothly, preventing cross-threading and speeding up the assembly process. This small feature is especially useful in field applications where alignment can be challenging.

Bolt

A bolt is a type of threaded fastener with an external male thread. It is designed to pass through an unthreaded hole in an assembly and be secured by a nut. Bolts create clamping force by stretching along their axis when tightened. This tension holds components, like two flanges, firmly together.

Bolt Head

The bolt head is the enlarged, pre-formed end of a bolt. It serves two primary purposes. First, it provides a surface for a tool, such as a wrench or socket, to grip and apply torque. Second, the underside of the head acts as a bearing surface, transferring the bolt’s tension into clamp load on the joint. Head styles vary, with hex and heavy hex being common for industrial applications.

Bolt Shank

The bolt shank is the smooth, unthreaded portion of the bolt between the head and the threads. The diameter of the shank is typically the nominal diameter of the bolt. This section provides the primary resistance against shear forces, which are forces that try to slice the bolt sideways. The length of the shank contributes to the bolt’s overall grip length.

Bolt Threads

Bolt threads are the helical ridges that spiral around the end of the bolt’s body. These ridges engage with the matching internal threads of a nut or a tapped hole. The precise geometry of the threads, including their pitch and angle, determines how torque translates into axial tension.

Key Function: Threads are the mechanism that allows a bolt to be tightened. As the nut turns, it travels along the threads, stretching the bolt and creating the necessary clamping force to secure the joint.

Bolt Grade

A bolt grade is a standardized classification that defines a bolt’s mechanical properties. It is a crucial specification that tells an engineer about the fastener’s strength. Key properties defined by a grade include:

- Tensile Strength: The maximum stretching force the bolt can withstand before breaking.

- Yield Strength: The point at which the bolt begins to deform permanently.

- Hardness: The material’s resistance to indentation and wear.

Standards organizations like ASTM and SAE establish these grades. For example, ASTM A193 Grade B7 is a common specification for high-strength alloy steel flange bolts used in high-pressure and high-temperature service. Selecting the correct grade ensures the flange bolts can handle the operational loads of the system safely.

Bolt-Up

Bolt-up is the comprehensive process of securing a bolted flange joint. This procedure involves much more than simply tightening bolts; it is a systematic method designed to achieve a specific, uniform clamp load across the entire joint. A successful bolt-up ensures the gasket is compressed evenly, creating a reliable, leak-free seal capable of withstanding the system’s operational pressures and temperatures.

Technicians follow a precise sequence to guarantee joint integrity. Key elements of a proper bolt-up procedure include:

- Inspection and Cleaning: Technicians inspect all components, including bolt threads, nut faces, and flange surfaces, for damage or defects. They clean all surfaces to remove contaminants.

- Lubrication: A specified lubricant is applied to bolt threads and bearing surfaces. This reduces friction and helps achieve the target bolt tension accurately.

- Tightening Pattern: Bolts are tightened in a star or crisscross pattern. This method distributes the load evenly across the gasket.

- Multiple Passes: The final torque or tension is applied in several stages. For example, technicians might apply 30%, 60%, and then 100% of the target torque in successive passes.

Carbon Steel

Carbon steel is an iron alloy where carbon is the primary alloying element. The amount of carbon in the steel directly dictates its mechanical properties. A higher carbon content generally increases the material’s hardness and tensile strength but reduces its ductility and weldability. Manufacturers classify carbon steel into different categories based on carbon percentage.

For fasteners, the choice of carbon steel grade is critical. Low-carbon steel is often used for general-purpose, low-strength bolts, while medium and high-carbon steels are heat-treated to produce high-strength fasteners.

Note: The carbon content is the main differentiator, but other elements like manganese and silicon are also controlled to achieve desired properties.

| Steel Type | Carbon Content (%) | Manganese Content (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Low Carbon Steel | 0.04 – 0.30 | 0.35 – 0.65 |

| Medium Carbon Steel | 0.30 – 0.60 | 0.50 – 1.65 |

| High Carbon Steel | > 0.60 | N/A |

Chamfer

A chamfer is a small, angled cut made on an edge or corner of a fastener. On bolts and studs, a chamfer is typically applied to the threaded end. This slight bevel creates a conical tip that serves a crucial function during assembly. It guides the bolt into a nut or tapped hole, making it significantly easier to start the threads.

The presence of a chamfer helps prevent cross-threading, a common issue where threads misalign and become damaged. By ensuring a smooth start, a chamfer speeds up installation and reduces the risk of fastener damage, especially in field applications where perfect alignment can be difficult. It is a simple but essential feature for efficient and reliable bolted connections.

Clamp Load

Clamp load is the compressive force exerted on a joint by a tightened fastener. This force, also known as preload or axial tension, is what holds the flange assembly together and ensures the gasket creates a tight seal. Achieving the correct clamp load is the primary objective of any bolting procedure. Insufficient load can lead to leaks, while excessive load can damage the bolt, flange, or gasket.

Engineers calculate the minimum required clamp load for a gasketed joint by determining two key values, Wm1 and Wm2. The greater of these two values dictates the minimum design bolt load.

- Wm1 is the load needed to maintain a seal against hydrostatic end forces during operation.

- Wm2 is the minimum load required to properly seat the gasket during assembly.

It is important to note that installation loads are often significantly higher than these minimum design values. Technicians should contact the gasket manufacturer to obtain specific recommended installation loads for their application.

Coating

A coating is a layer of material applied to the surface of a fastener. Manufacturers apply coatings to enhance specific properties, primarily to improve corrosion resistance, reduce friction, or provide chemical resistance. The choice of coating depends on the service environment and performance requirements.

Cadmium Plating

Cadmium plating is a metallic coating that provides excellent corrosion resistance, especially in marine or salt-rich environments. It also offers good lubricity, which helps achieve consistent clamp loads. However, due to its toxicity, environmental regulations heavily restrict its use.

Hot-Dip Galvanizing (HDG)

Hot-dip galvanizing involves immersing steel fasteners in a bath of molten zinc. This process creates a thick, durable, and abrasion-resistant coating of zinc alloy layers. HDG offers robust, long-term corrosion protection, making it ideal for outdoor and industrial applications.

PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene)

PTFE coatings, often known by the brand name Teflon®, provide a low-friction surface with outstanding chemical resistance. Technicians use these coatings in corrosive environments to prevent thread galling and ensure predictable torque values. The low friction coefficient means less torque is needed to achieve the desired preload.

Zinc Plating

Zinc plating, or electro-galvanizing, is a process where a thin layer of zinc is applied to a fastener using an electric current. It provides a moderate level of corrosion protection and is a cost-effective option for fasteners used in mild or indoor environments.

Corrosion

Corrosion is the gradual degradation of a material, typically a metal, due to chemical or electrochemical reactions with its environment. For flange bolts, corrosion weakens the fastener, reduces its load-bearing capacity, and can ultimately lead to joint failure. One of the most common forms in bolted assemblies is galvanic corrosion.

Galvanic corrosion occurs when two dissimilar metals are in contact within an electrolyte. This contact creates a galvanic cell, which accelerates the corrosion of one metal. The process requires four components:

- Anode: The more reactive metal that corrodes.

- Cathode: The less reactive metal that is protected.

- Return Current Pathway: The direct contact between the two metals.

- Electrolyte: A conductive fluid, such as moisture or rainwater, that connects the metals.

A significant difference in electrical potential between the metals acts as the driving force for this accelerated corrosion.

Creep

Creep is the slow, permanent deformation of a material subjected to constant stress at high temperatures. In bolted flange connections, this phenomenon is a critical concern. It causes a gradual loss of the bolt’s initial tension, a process known as stress relaxation. Even when stress levels are well below the material’s yield strength, high temperatures can cause the bolt’s elastic strain (the stretch that creates clamp load) to convert into permanent plastic strain. This irreversible stretching reduces the clamping force on the gasket, potentially leading to leaks and joint failure.

Engineers must carefully consider the operational temperature when selecting bolt materials to mitigate the effects of creep. Different materials have different temperature thresholds at which creep becomes a significant risk.

Temperature and Material Selection Carbon steel bolts, for example, may begin to experience significant creep and stress relaxation at temperatures above 400°F (204°C). In contrast, alloy steel bolts, such as ASTM A193 Grade B7, are designed to resist creep at much higher temperatures, often up to 840°F (450°C). For even more extreme service conditions, specialized chrome-moly alloys like Grade B16 are required.

The integrity of a bolted joint depends on maintaining adequate clamp load over its service life. Several factors related to temperature can compromise this integrity:

- Exceeding the designed operational temperature range of the fasteners accelerates creep and stress relaxation.

- The mechanical strength properties of all fasteners, including tensile and yield strength, decline as temperatures rise.

- A mismatch in the thermal expansion coefficients between the bolt material and the flange material can cause significant changes in clamping force during thermal cycling.

Ultimately, selecting the correct bolt material specified for the system’s maximum operating temperature is the primary defense against creep. This ensures the bolted joint remains secure, tight, and leak-free throughout its intended lifecycle.

Glossary Terms: D – G

This section explores key terms from D to G. It covers the critical dimensions of a bolt, a material’s electrical properties, and its ability to stretch under load.

Diameter

Diameter is a fundamental measurement for any fastener. Engineers use several specific diameter measurements to define a bolt’s dimensions and ensure proper fit and function.

Major Diameter

The major diameter is the largest diameter of a screw thread. Technicians measure this dimension from the crest (top) of the thread on one side to the crest on the opposite side. It is the primary dimension used to identify a thread size.

Minor Diameter

The minor diameter, also known as the root diameter, is the smallest diameter of a screw thread. This measurement is taken from the root (bottom) of the thread on one side to the root on the other. It is a critical factor in calculating the bolt’s tensile stress area.

Nominal Diameter

The nominal diameter is the general size used to identify a fastener. For example, a “1/2-inch bolt” refers to its nominal diameter. This dimension typically corresponds to the major diameter of the threads. It provides a simple, standardized way to specify and procure bolts.

Dielectric Strength

Dielectric strength measures a material’s ability to withstand electrical voltage without breaking down and conducting electricity. It is a critical property for insulating materials used in bolted flange connections.

Application in Flange Isolation: Materials with high dielectric strength, such as those used in flange isolation kits, act as non-conductive barriers. They electrically separate the flanges and bolts. This separation is essential for preventing galvanic corrosion between dissimilar metals.

Elongation

Elongation is a measure of a material’s ductility. It quantifies how much a fastener can stretch or deform under tensile load before it fractures. Engineers express this value as a percentage of the bolt’s original length. A higher elongation percentage indicates a more ductile material that can absorb more energy before failing.

This property is vital for safety. Ductile bolts provide a visual warning of overload by stretching noticeably, whereas brittle materials can snap suddenly without warning. For example, ASTM A325 specifications require a minimum elongation of 14% for many common sizes. This requirement ensures sufficient ductility to prevent brittle failures and maintain joint flexibility in structural applications. The table below details these minimums for the F3125 Grade A325 specification.

| Specification | Size Range | Elongation %, min |

|---|---|---|

| F3125 Grade A325 | 1/2″ – 1″ | 14 |

| F3125 Grade A325 | 1 1/8″ – 1 1/2″ | 14 |

Sufficient elongation allows a bolted joint to flex under dynamic loads, distributing stress and preventing catastrophic failure.

Embedment

Embedment is the localized plastic deformation, or crushing, that occurs on the surfaces of a joint under the high compressive stress of a tightened fastener. This microscopic flattening happens on the bearing surfaces under the bolt head and nut, as well as on the flange faces themselves.

As the bolt is tightened, the immense pressure causes the high points on the metal surfaces to yield and settle. This settling results in a small loss of bolt stretch, which directly reduces the clamp load.

Note: Embedment is a primary cause of short-term preload loss, often occurring within minutes or hours of initial bolt-up. This is why many critical joint procedures specify a re-torquing pass after a set period to compensate for this initial relaxation.

Fastener

A fastener is a hardware device that mechanically joins or affixes two or more objects. This broad category includes a wide range of components designed to create non-permanent joints, meaning the objects can be separated without damage.

Common types of fasteners include:

- Bolts

- Screws

- Nuts

- Studs

- Washers

In the context of flanged connections, the term “fastener” typically refers to the combination of bolts or studs, nuts, and washers used to secure the joint.

Fatigue

Fatigue is the progressive and localized structural damage that occurs when a material is subjected to repeated or fluctuating loads (cyclic loading). This process can cause a fastener to fail at a stress level significantly lower than its rated tensile strength. Fatigue failure is particularly dangerous because it often happens suddenly and without any prior visible deformation.

The failure process typically starts at a point of high stress concentration. For flange bolts, several factors create these high-stress points and contribute to fatigue:

- High stress concentration at the thread root, especially where the thread runout occurs.

- Bending stresses induced in the threads during load transfer between the nut and bolt.

- Uneven load distribution across the thread faces.

- The manufacturing method, as cut threads can create sharper notches than rolled threads.

Other factors that accelerate fatigue failure include underlying material defects, corrosion that creates surface pits, and improper installation that results in incorrect or uneven preload. Systems exposed to high cyclic loads, such as those in vibrating machinery or structures subject to wind, are especially susceptible to fastener fatigue.

Flange

A flange is a protruding rim or lip used to connect pipes, valves, pumps, and other equipment to form a piping system. These connections allow for easier assembly, disassembly, and maintenance.

Blind Flange

A blind flange is a solid disk used to block off a pipeline or seal a vessel opening. It has mounting holes around the perimeter but no central opening. Technicians use it to terminate a piping system or to provide future access.

Lap Joint Flange

A lap joint flange is a two-piece assembly consisting of a stub end and a loose backing flange. The stub end is welded to the pipe, and the flange then slides over it. This design allows the flange to rotate for easy bolt hole alignment.

Slip-On Flange

A slip-on flange slides over the pipe and is then welded in place. Technicians perform welds on both the inside and outside of the flange to provide strength and prevent leakage. These are easy to align and are a cost-effective choice.

Socket Weld Flange

A socket weld flange has a recessed shoulder on the inside. The pipe fits into this socket, and technicians apply a fillet weld around the top. This design is common for smaller, high-pressure piping.

Threaded Flange

A threaded flange has internal threads that screw onto a pipe with matching external threads. This type of flange allows for assembly without welding, making it suitable for low-pressure applications and highly explosive areas where welding is hazardous.

Weld Neck Flange

A weld neck flange features a long, tapered hub that is butt-welded to the pipe. This design transfers stress from the flange to the pipe itself, providing superior strength for high-pressure and high-temperature applications.

Flange Face

The flange face is the machined surface where a gasket is seated to create a seal. The type of face determines the kind of gasket used and the joint’s performance characteristics.

Flat Face (FF)

A flat face flange has a contact surface that is level with the bolting circle plane. These flanges require full-face gaskets that cover the entire flange surface. They are typically used in low-pressure, low-temperature applications.

Raised Face (RF)

A raised face flange has a small portion of the face raised above the bolting circle. This design concentrates the pressure from the flange bolts onto a smaller gasket area, increasing the pressure-containing capability of the joint.

Ring-Type Joint (RTJ)

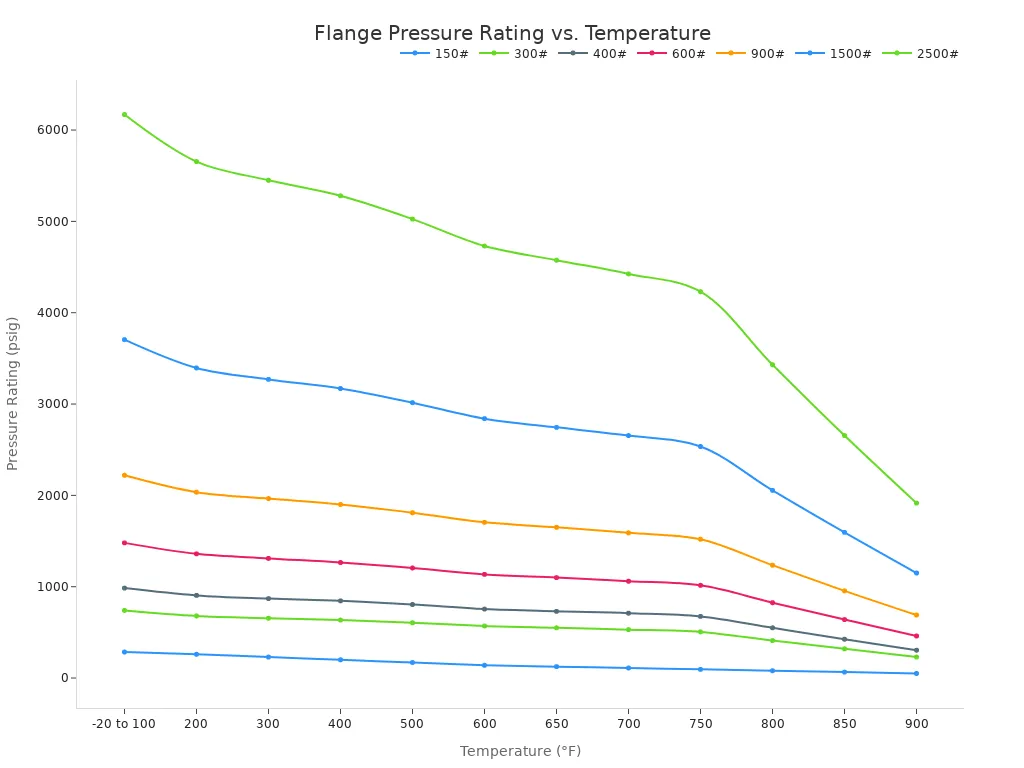

Ring-Type Joint (RTJ) flanges are typically utilized in high-pressure services, specifically Class 600 and higher ratings, and/or in high-temperature applications exceeding 800°F (427°C). These flanges feature grooves on their faces designed to accommodate steel ring gaskets. The tightening of the bolts compresses the gasket to form a highly effective metal-to-metal seal. The allowable pressure for any flange class decreases as the operating temperature increases.

ASME B16.5 Pressure-Temperature Ratings for A105 Carbon Steel Flanges (psi)

| Temperature (°F) | 150# | 300# | 600# | 900# | 1500# | 2500# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -20 to 100 | 285 | 740 | 1480 | 2220 | 3705 | 6170 |

| 400 | 200 | 635 | 1265 | 1900 | 3170 | 5280 |

| 800 | 80 | 410 | 825 | 1235 | 2055 | 3430 |

Gasket

A gasket is a mechanical seal that fills the space between two mating surfaces. It creates a seal by yielding under compression. In flange design, engineers use two critical constants, ‘m’ and ‘y’, to ensure proper gasket performance.

- The ‘y’ constant represents the minimum compressive stress needed to seat the gasket and fill surface imperfections.

- The ‘m’ factor is a multiplier used to calculate the additional load required to maintain the seal against internal system pressure.

Full Face Gasket

A full face gasket covers the entire surface of a flange and includes holes for the bolts to pass through. It is primarily used with flat face flanges.

Ring Gasket

A ring gasket is a flat ring of material that fits inside the bolt circle of a raised face flange. It is the most common type of gasket for these flanges.

Spiral Wound Gasket

A spiral wound gasket is a semi-metallic gasket made from a V-shaped metal strip spirally wound with a soft filler material. This construction gives it excellent resilience, making it ideal for high-pressure and high-temperature applications.

Grade (of a bolt)

A bolt grade is a standard classification that defines the mechanical properties of a fastener. This specification is crucial because it communicates the bolt’s strength and performance capabilities. Engineers rely on the grade to select a fastener that can safely handle the design loads of a specific application. Key properties dictated by a bolt’s grade include its tensile strength, yield strength, and hardness.

Standards organizations like ASTM and SAE establish these grades to ensure consistency and reliability across the industry. For example, ASTM A193 Grade B7 is a common specification for high-strength alloy steel bolts used in high-pressure and high-temperature service. Choosing the correct grade is a critical step in ensuring the safety and integrity of a bolted flange connection.

Common ASTM Bolt Grades and Their Applications The material, strength, and intended service environment vary significantly between grades. Technicians must select the appropriate grade to match the operational demands of the piping system.

| Grade | Material | Min. Tensile Strength (ksi) | Common Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASTM A307 | Carbon Steel | 60 | General purpose, low-pressure, and non-critical applications. |

| ASTM A193 B7 | Alloy Steel, Cr-Mo | 125 | High-temperature, high-pressure service in refineries and power plants. |

| ASTM A320 L7 | Alloy Steel, Cr-Mo | 125 | Low-temperature and cryogenic service where toughness is required. |

Grip Length

The grip length is the distance from the underside of the bolt head to the beginning of the thread. It represents the unthreaded portion of the bolt shank that is clamped within the joint. This dimension is a critical factor in the performance and reliability of a bolted connection because it is the primary section of the fastener that stretches to generate clamp load.

A bolt with a longer grip length behaves more like a spring, offering greater elasticity. This property is highly desirable for maintaining a stable preload.

Why Grip Length Matters The ratio of a bolt’s grip length to its diameter (L/D) directly impacts its ability to maintain clamp load. A higher L/D ratio is preferred because it makes the joint more reliable.

- Reduces Preload Loss: Bolts with longer grip lengths are less affected by preload loss from factors like embedment and thermal expansion. Joints with a low L/D ratio can lose 15% to 30% of their initial preload from embedment alone.

- Resists Loosening: A longer bolt is more elastic and can bend slightly to absorb small transverse movements without the nut or head slipping. This flexibility makes the joint more resistant to loosening caused by vibration or side loads.

- Increases Elasticity: The longer a bolt’s effective length, the more it can stretch for a given load. This increased elasticity allows it to better compensate for gasket creep and relaxation over time, ensuring a more durable and leak-free seal.

Glossary Terms H – N: Hardness, Head Styles, and Heavy Hex Flange Bolts

This section covers essential terms from H to N. It details material hardness, common bolt head designs, and the critical processes of heat treatment that define a fastener‘s final properties.

Hardness

Hardness measures a material’s resistance to localized plastic deformation, such as scratching or indentation. For fasteners, hardness correlates directly with tensile strength and wear resistance. Technicians use standardized tests to measure and verify this crucial property.

Brinell Hardness

The Brinell hardness test involves pressing a hard metal ball of a specific diameter into a material’s surface with a predetermined force. After removing the load, technicians measure the diameter of the resulting indentation. The Brinell Hardness Number (HBW) is calculated based on the indentation size, providing a measure of the material’s macro-hardness over a larger area.

Rockwell Hardness

The Rockwell hardness test measures the depth of an indentation made by a specific indenter under a fixed load. It is a faster and simpler test than Brinell, making it widely used for quality control. The result is read directly from a scale (e.g., HRC for harder materials, HRB for softer ones). Different bolt grades have specific hardness requirements.

| Grade | Hardness (Rockwell) |

|---|---|

| B7 | 35 max HRC |

| B8 Class 1 | 96 max HRB |

| B8 Class 2 | 35 max HRC |

Head Style

The head style refers to the shape of the top of the bolt. This design provides a surface for a tool to apply torque and acts as a bearing surface to distribute the clamp load.

Hex Head

A hex head is a six-sided head, making it the most common style for bolts and screws. Its geometric shape allows for easy gripping with wrenches and sockets from multiple angles.

Heavy Hex Head

A heavy hex head is larger and thicker than a standard hex head. This increased size provides a greater bearing surface, which helps distribute the clamping force more effectively. Manufacturers commonly use this style for high-strength structural and flange bolts.

Square Head

A square head features four sides. While less common today, it offers a large gripping surface and can be tightened with a simple wrench. This design is sometimes found in older machinery and specific applications where maximum grip is needed.

Heat Treatment

Heat treatment is a controlled process of heating and cooling metals to alter their physical and mechanical properties. This process allows manufacturers to achieve a desired balance of hardness, strength, and ductility in a fastener.

Annealing

Annealing is a heat treatment process where a material is heated to a specific temperature, held there, and then slowly cooled. This procedure softens the metal, increases its ductility, and relieves internal stresses, making it easier to machine or form.

Quenching

Quenching involves heating steel to a high temperature and then cooling it rapidly in a medium like oil or water. This process locks in a hard, brittle crystalline structure. Hardening heat treatments like quenching increase a fastener’s strength but significantly reduce its ductility.

Tempering

Tempering is a secondary heat treatment performed after quenching. Technicians reheat the hardened fastener to a lower temperature and hold it for a set time. This process reduces some of the extreme hardness and brittleness from quenching but critically increases the material’s ductility and toughness. The combination of quenching and tempering allows engineers to fine-tune a bolt’s properties for optimal performance.

Hydrogen Embrittlement

Hydrogen embrittlement is a failure mechanism where high-strength steel loses its ductility and becomes brittle after absorbing atomic hydrogen. This condition can lead to sudden, catastrophic failure of a fastener under load, often well below its specified tensile strength. The risk of hydrogen embrittlement increases significantly when three specific conditions are met.

- Presence of hydrogen: Sufficient hydrogen must be available to penetrate the steel. Common sources include manufacturing processes like galvanizing, environmental corrosion, and high-pressure service conditions.

- Susceptibility of a material: High-strength steels are more prone to this issue. Their microstructure allows them to absorb and trap hydrogen atoms more easily, increasing the risk of cracking.

- Stress: Applied tensile stress, whether from external loads or internal residual stress, helps hydrogen atoms migrate to critical areas like microcracks, initiating failure.

A material’s core hardness is a key indicator of its susceptibility. As hardness increases, so does the risk.

| Core Hardness (HV) | Risk of Hydrogen Embrittlement |

|---|---|

| Below 360 | Minimal (though not eliminated) |

| Between 360 and 390 | Manageable with evaluation and mitigation |

| Above 390 | Significantly increased, requiring thorough assessment |

K-Factor (Nut Factor)

The K-Factor, or nut factor, is a dimensionless constant used in torque calculations to account for friction. It is a critical variable in the formula T = K * d * F, which relates applied torque (T) to the resulting bolt preload or clamp load (F). The K-Factor simplifies the complex friction effects at the thread and bearing surfaces into a single, experimentally determined value.

Friction can consume up to 90% of the applied torque, making the K-Factor essential for achieving an accurate preload. This factor is not universal; it changes based on the fastener’s material, size, surface finish, and especially the type of lubricant used. For example, tests on a 5/8-inch bolt showed an unlubricated K-Factor of 0.25. Applying a MOLYKOTE lubricant reduced the K-Factor to 0.16, demonstrating how lubrication dramatically alters the torque-tension relationship.

Note: An accurate K-Factor can only be determined through experiments using the specific fastener, nut, washer, and lubricant intended for the application. Technicians should use published K-Factor tables with extreme caution and always verify their applicability.

Load Indicating Washer

A load indicating washer, also known as a Direct Tension Indicator (DTI), is a specialized hardened washer that provides a visual and mechanical method for verifying bolt tension. These washers feature small protrusions on one face. As a technician tightens the bolt, the increasing clamp load flattens these protrusions.

The washer is designed so that the protrusions compress to a specific gap when the bolt reaches its required minimum tension. A technician can then use a feeler gauge to check this gap, confirming that the proper preload has been achieved. This simple inspection provides a reliable way to ensure joint integrity without relying on torque measurements, which can be inaccurate due to friction variables. DTIs are commonly used in structural steel connections where correct bolt tension is a critical safety requirement.

Lubricant

A lubricant is a substance that technicians apply to fastener threads and bearing surfaces before tightening. Its primary purpose is to reduce friction. This reduction allows a greater percentage of the applied torque to be converted into useful clamp load, or bolt stretch. Without proper lubrication, friction can consume up to 90% of the tightening energy, leading to inaccurate and insufficient preload.

The type of lubricant significantly impacts the torque-tension relationship. Different lubricants have different friction coefficients, which must be accounted for in torque calculations.

Note: Using a specified lubricant and applying it consistently is one of the most critical steps for achieving a reliable and leak-free bolted joint. It ensures that the torque values used during bolt-up produce the intended clamp load.

Nut

A nut is a fastener with a threaded hole. It pairs with a bolt, stud, or screw that has a matching external thread. When a technician applies torque to a nut, it travels along the bolt’s threads. This action stretches the bolt, generating the axial tension required to clamp a joint together. Nuts come in various styles, with the design chosen based on the application’s strength and environmental requirements.

Heavy Hex Nut

A heavy hex nut is dimensionally larger than a standard hex nut. It is both thicker and wider across its flats. This increased size serves two key functions:

- It provides a larger bearing surface to distribute the clamp load more effectively.

- It has greater strength to match high-strength bolts.

Manufacturers design heavy hex nuts for use in high-pressure and high-temperature services. They are the standard choice for most industrial applications involving structural steel and high-strength flange bolts.

Hex Nut

A hex nut is the most common type of nut, featuring a standard six-sided shape. Technicians use it for a wide range of general-purpose fastening applications. While suitable for many connections, it lacks the larger bearing surface and higher proof load strength of a heavy hex nut. Its use is typically limited to lower-strength bolts and less critical joints.

Jam Nut

A jam nut is a thinner version of a hex nut. Technicians use it as a locking device to prevent a primary nut from loosening due to vibration or dynamic loads. The jam nut is typically installed first and tightened to a low torque value. Then, the standard nut is tightened against it. This “jams” the two nuts together, creating a secure connection that resists rotation.

Nominal Pipe Size (NPS)

Nominal Pipe Size (NPS) is a North American set of standard sizes for pipes used for high or low pressures and temperatures. The term “nominal” indicates that the size is a name rather than an exact measurement. The NPS is a critical reference because flange dimensions are directly tied to the NPS and pressure class of the pipe.

Important Distinction: For pipe sizes under 12 inches, the NPS is smaller than the actual outside diameter (OD) of the pipe. For pipe sizes 14 inches and larger, the NPS is equal to the pipe’s OD. This standard ensures that pipes and flanges from different manufacturers are compatible.

Glossary Terms: P – S

This section covers key terms from P to S. It explains a critical surface treatment for stainless steel, the geometry of threads, and the fundamental force that holds a bolted joint together.

Passivation

Passivation is a chemical treatment process that enhances the natural corrosion resistance of stainless steel fasteners. While stainless steel is inherently corrosion-resistant due to its chromium content, its surface can be compromised during manufacturing. Contaminants like free iron particles from cutting tools can adhere to the surface and become sites for rust to begin.

The passivation process removes these contaminants and maximizes the material’s protective capabilities. Technicians immerse the stainless steel fasteners in a mild acid bath, typically nitric or citric acid. This treatment accomplishes two critical goals:

- It dissolves free iron and other contaminants from the surface without harming the stainless steel itself.

- It promotes the formation of a uniform, stable, and thicker chromium oxide layer.

This passive film is an inert, non-reactive barrier that shields the base metal from moisture and other corrosive elements. It ensures the fastener achieves its maximum potential for longevity and performance, especially in harsh service environments.

Pitch (Thread Pitch)

Pitch is the distance from a point on one screw thread to the corresponding point on the next adjacent thread. Technicians measure this distance parallel to the bolt’s axis. It is a fundamental parameter that defines how fine or coarse the threads are. In Unified Inch Screw Threads (UNC/UNF), pitch is often expressed as Threads Per Inch (TPI). A bolt with 12 TPI has a pitch of 1/12th of an inch.

The choice between a coarse or fine pitch depends on the application’s requirements.

- Coarse Threads (UNC): These threads have a larger pitch. They are more common, install faster, and are less susceptible to cross-threading or damage.

- Fine Threads (UNF): These threads have a smaller pitch. They offer greater tensile strength and better resistance to loosening from vibration due to their smaller helix angle.

Note: A finer pitch allows for more precise tension adjustments. However, the threads are more delicate and require more care during assembly to avoid galling.

Preload

Preload is the tension created in a bolt as it is tightened. This stretching force, also known as clamp load or axial tension, is what holds a bolted joint together. Achieving the correct amount of preload is the primary objective of any controlled bolting procedure. This internal force must be great enough to compress the gasket, create a seal, and resist any external forces trying to separate the flanges.

When a technician applies torque to a nut, the bolt stretches like a stiff spring. This stored elastic energy generates the clamping force on the joint.

- Insufficient Preload: If the preload is too low, the joint may leak under pressure or loosen due to vibration.

- Excessive Preload: If the preload is too high, it can exceed the bolt’s yield strength, causing permanent damage. It can also crush the gasket or damage the flange faces.

Properly calculated and applied preload is therefore essential for the safety, reliability, and leak-free performance of a bolted flange connection.

Pressure Class

A Pressure Class is a standardized rating that defines the maximum pressure a flange can safely withstand at a given temperature. Organizations like ASME establish these classes to ensure the safety and interchangeability of piping components. Common pressure classes include 150, 300, 400, 600, 900, 1500, and 2500.

This rating is not a single pressure value. It represents a pressure-temperature curve. As the operating temperature of a system increases, the flange material loses strength, and its maximum allowable working pressure decreases. For example, a Class 300 carbon steel flange might handle 740 psi at ambient temperature but only 635 psi at 400°F. Engineers must select a flange and its corresponding bolts with a pressure class that exceeds the system’s maximum operating pressure and temperature to ensure a safe and reliable joint.

Proof Load

Proof load is a specific tensile load applied to a fastener during quality control testing. This test verifies that the fastener can withstand a high load without experiencing permanent deformation. It is a critical pass/fail assessment that confirms the fastener’s manufacturing quality and its ability to perform under service conditions. Proof load is a test value applied to a finished component, not an inherent property of the material itself.

It is often confused with yield strength, but the two concepts are distinct. Yield strength is an intrinsic material property, while proof load is a verification test.

| Feature | Yield Strength | Proof Load |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | The stress at which a material begins to deform permanently. | A specified load applied to a component to verify its quality without causing permanent damage. |

| Nature | An inherent property of the material itself. | A test value applied to a specific component, like a bolt or nut. |

| Application | Used in design calculations for structural safety. | Used in quality assurance to confirm a component’s performance capability. |

The proof load test was developed as a practical alternative to yield testing for full-size fasteners.

- Technicians subject a headed bolt to a specific load, typically 90-93% of its minimum yield strength.

- The load is held for a set duration, often 10 seconds.

- The fastener passes if it does not elongate more than a specified amount (e.g., 0.0005 inches) after the load is removed.

Relaxation

Relaxation is the gradual loss of initial bolt preload over time after the tightening process is complete. This loss of tension occurs without any external load changes and can compromise the integrity of a bolted joint. It is a critical concern because it reduces the clamping force on the gasket, potentially leading to leaks.

Several factors contribute to relaxation:

- Embedment: The microscopic flattening of high points on the bearing surfaces under the nut, bolt head, and on the flange faces.

- Gasket Creep: The gradual compression and thinning of the gasket material under constant load.

- Thermal Effects: Differential thermal expansion and contraction between the bolt and flange materials during temperature cycles.

- Vibration: Dynamic loads that can cause slight rotational loosening of the nut.

Relaxation is the result of these combined effects. It represents the conversion of the bolt’s elastic stretch into non-functional plastic deformation within the joint components. Proper material selection, joint design, and re-tightening procedures can help mitigate its impact.

Root (of a thread)

The root is the bottom surface that joins the flanks of two adjacent threads. It forms the valley between the thread crests. This small area is one of the most critical features of a bolt because it is a point of high stress concentration. When a bolt is under tension, forces concentrate at the root, making it a common point for fatigue cracks to begin.

The geometry of the root significantly influences a fastener’s fatigue life. A rounded root profile distributes stress more evenly than a sharp, V-shaped root. This improved stress distribution greatly enhances the bolt’s resistance to failure under cyclic loading. Manufacturing processes like thread rolling naturally create a radiused root with a superior grain structure. This makes rolled threads generally more durable than cut threads, which can leave sharp corners and microscopic tool marks that act as stress risers. Proper root design is therefore essential for producing reliable, high-performance fasteners.

Runout

Runout measures the total variation of a surface as a part rotates around a central axis. It essentially quantifies how much a feature, like a bolt head or thread, deviates or “wobbles” from its ideal circular path. Inspectors use a dial indicator to measure this imperfection. Excessive runout can indicate manufacturing defects and may lead to problems in a bolted connection, such as uneven load distribution and increased vibration.

There are two primary types of runout measurement:

- Circular Runout: This measures the variation at a single circular cross-section. It controls the roundness and concentricity of a feature at one specific point.

- Total Runout: This measures the variation across an entire surface as the part rotates. It provides a more comprehensive control of the feature’s form, orientation, and location.

For fasteners, controlling runout on the bearing surface of the head and nut is critical. It ensures the clamp load is applied evenly to the flange face.

Shank

The shank is the smooth, unthreaded portion of a bolt located between the head and the start of the threads. The diameter of the shank is typically equal to the nominal diameter of the bolt. This section of the fastener serves two vital functions in a bolted joint.

First, the shank provides the primary resistance against shear forces. Shear forces are loads that attempt to slice a bolt sideways. The solid, full-diameter cross-section of the shank is stronger against these forces than the threaded portion. Second, the shank’s length contributes to the bolt’s overall grip length.

A longer shank increases the bolt’s elasticity. This allows the fastener to stretch more like a spring, making it better at maintaining preload and resisting loosening from vibration or thermal cycling.

Engineers often specify bolts with a longer shank for critical applications to improve the joint’s overall reliability and performance.

Shear Strength

Shear strength measures a fastener’s capacity to resist forces that try to slice it in half across its axis. This is different from tensile strength, which measures resistance to being pulled apart. In a bolted joint, shear forces occur when the connected parts try to slide past one another.

Engineers commonly estimate a bolt’s shear strength to be around 60% of its minimum tensile strength. The Industrial Fastener Institute (IFI) supports this approximation. This ratio is rooted in material science principles like the von Mises yield criterion, which suggests a theoretical relationship of about 0.58 between tensile and shear yield strengths. While the 60% rule is a reliable guideline, the actual value can vary slightly based on the material grade and specific application conditions.

Stainless Steel

Stainless steel is an iron-based alloy containing a minimum of 10.5% chromium. The chromium creates a thin, passive oxide layer on the surface that provides excellent corrosion resistance. This property makes stainless steel a preferred material for fasteners used in corrosive or high-purity environments.

304 Stainless Steel

Often called “18-8” stainless steel, 304 contains approximately 18% chromium and 8% nickel. It is the most widely used grade of stainless steel. It offers good corrosion resistance to a wide range of atmospheric and chemical exposures, making it a versatile and cost-effective choice for many applications.

316 Stainless Steel

316 stainless steel builds upon the properties of 304 by adding molybdenum (typically 2-3%). This addition significantly enhances its resistance to corrosion, especially from chlorides and other industrial solvents. This makes 316 the superior choice for marine environments, chemical processing plants, and other highly corrosive settings.

ASTM A193 Grade B8/B8M

This ASTM specification covers stainless steel bolting for high-temperature or high-pressure service. The grades directly correspond to the stainless steel types:

- Grade B8 fasteners are manufactured from 304 stainless steel.

- Grade B8M fasteners are manufactured from 316 stainless steel. This standard ensures that the fasteners meet specific mechanical property and testing requirements for demanding industrial use.

Stud Bolt

A stud bolt is a threaded fastener without a head. It is essentially a rod threaded on both ends. Technicians use stud bolts to join two flanges by passing the stud through both flange holes and securing it with a nut on each end.

Fully Threaded Stud Bolt

A fully threaded stud bolt has threads running along its entire length. This design provides maximum thread engagement for the nuts, making it a common choice for general-purpose flange connections.

Double-End Stud Bolt

A double-end stud bolt features a plain, unthreaded shank in the middle with threaded sections on both ends. The threads on each end can be of equal or different lengths. This type is often used in applications where a specific grip length is required or where one end is screwed into a tapped hole.

Surface Finish

Surface finish describes the texture of a fastener’s surface, including its roughness, waviness, and lay. It refers to the microscopic peaks and valleys created during the manufacturing process. Engineers measure this texture to control its impact on a fastener’s performance. The most common measurement is Roughness Average (Ra), which calculates the average height of these microscopic irregularities across a surface. A lower Ra value indicates a smoother, more refined surface, while a higher Ra value signifies a rougher texture.

The condition of a fastener’s surface is a critical engineering parameter. It is not merely a cosmetic feature. The surface finish directly influences several key aspects of a bolted joint’s performance and reliability.

Friction and Torque-Tension Relationship: The surface texture on the threads and bearing surfaces is a primary factor in determining the friction coefficient. A rougher surface generally creates more friction. This means more of the applied torque is lost overcoming friction, and less is converted into useful clamp load. A smooth, controlled surface finish helps achieve a more predictable and consistent torque-tension relationship.

Corrosion Resistance: Rough surfaces have more microscopic valleys where moisture, salt, and other corrosive agents can become trapped. These trapped contaminants create initiation sites for rust and other forms of corrosion. A smoother surface is easier to clean and provides fewer footholds for corrosive elements, enhancing the fastener’s longevity.

Fatigue Life: The microscopic valleys in a rough surface can act as stress risers. When a bolt is under cyclic or fluctuating loads, stress concentrates at these sharp points. This concentration can lead to the formation and propagation of fatigue cracks, potentially causing the fastener to fail prematurely. A smoother finish distributes stress more evenly and can significantly improve a bolt’s resistance to fatigue.

Technicians and engineers must recognize that surface finish is a functional property. Controlling it is essential for ensuring accurate preload, preventing corrosion, and maximizing the service life of critical bolted connections. The selection of a specific finish should align with the application’s environmental conditions and performance requirements.

Glossary Terms: T – Z

This final section covers terms from T to Z. It explains the specific ends of studs, the ultimate strength of a fastener, and the critical force that defines a secure connection.

Tap End

The tap end is the specific end of a double-end stud bolt designed to be screwed into a tapped (threaded) hole in a piece of equipment, such as a pump casing or engine block. This end often has a shorter thread length than the other end.

The tap end creates a semi-permanent connection with the equipment body. The other end, known as the nut end, protrudes from the equipment. Technicians then place a flange over the nut end and secure it with a nut. This design allows for easy removal of the flange without disturbing the stud’s connection to the main body.

Tensile Strength

Tensile strength measures the maximum pulling or stretching stress a material can withstand before it fractures or breaks. It represents the ultimate strength of the fastener material. Engineers express this value in pounds per square inch (psi) or megapascals (MPa). A bolt’s grade directly specifies its minimum tensile strength, which is a critical factor for ensuring a fastener can handle the design loads of an application.

Selecting a bolt with the appropriate tensile strength is essential for safety. A higher tensile strength indicates a stronger bolt capable of handling greater loads.

Minimum Tensile Strength for Common Bolt Grades

| ASTM Grade | Material Type | Minimum Tensile Strength (ksi) |

|---|---|---|

| A307 Grade A | Low Carbon Steel | 60 |

| A193 Grade B7 | Alloy Steel | 125 |

| A320 Grade L7 | Alloy Steel | 125 |

Tension

Tension is the stretching force, or load, created within a bolt as it is tightened. This force is also known as preload or clamp load. It is the critical force that holds a bolted joint together, compresses the gasket, and resists external forces trying to pull the flanges apart. Achieving the correct amount of tension is the primary goal of any controlled bolting procedure.

Technicians most often apply torque to a nut to generate this tension. However, the two are not the same.

Tension vs. Torque

- Torque is the rotational force applied to the nut. It is the input energy.

- Tension is the linear stretching force created in the bolt. It is the output or result.

A significant portion of torque is lost to friction at the threads and bearing surfaces. Therefore, tension is the true measure of a joint’s tightness, not torque.

Thread

A thread is the helical ridge that spirals around the body of a bolt or stud. These ridges engage with the internal threads of a nut or tapped hole. This mechanical interaction is what allows a fastener to be tightened, converting rotational motion into linear force.

Coarse Thread (UNC)

Coarse threads, standardized as Unified National Coarse (UNC), have a larger pitch and fewer threads per inch. This design makes them the most common choice for general industrial applications. Technicians find them faster to install and less prone to cross-threading or damage from handling. Their deeper threads offer better resistance to stripping.

Fine Thread (UNF)

Fine threads, or Unified National Fine (UNF), have a smaller pitch and more threads per inch. The smaller helix angle of fine threads provides better resistance to loosening from vibration. They also have a larger tensile stress area, making them slightly stronger in tension than their coarse-threaded counterparts. However, their delicate nature requires more care during assembly.

Thread Engagement

Thread engagement is the length of contact between the external threads of the bolt and the internal threads of the nut. Proper engagement is critical for distributing the load evenly across all threads. Insufficient engagement can concentrate stress on just a few threads, leading to stripping and joint failure. A general rule is that the engagement length should be at least equal to the nominal diameter of the bolt.

Thread Series

A thread series is a standardized system that defines the geometry of screw threads. It specifies parameters like diameter, pitch, and thread form. Systems like UNC and UNF ensure that bolts and nuts from different manufacturers are interchangeable. This standardization is fundamental to modern engineering and assembly.

Thread Galling

Thread galling is a form of severe adhesive wear that can occur when two metal surfaces slide against each other under high pressure. The friction and heat cause the surfaces to “cold-weld” together, seizing the fastener. This issue is especially common with stainless steel and other alloys that self-generate a protective oxide layer. Damaged threads can make disassembly impossible without destroying the fastener.

Technicians can prevent galling by following several key practices:

- Apply Proper Lubricants: Anti-seizing compounds or waxes create a barrier that reduces friction and heat.

- Slow the Tightening Speed: Using manual tools and a deliberate pace minimizes heat buildup. Power tools often generate excessive friction.

- Use Clean, Undamaged Fasteners: Dirt, debris, or damaged threads increase surface friction and the risk of seizing.

- Select Coarse Threads: UNC threads are less susceptible to galling than fine threads due to their larger thread clearance.

- Mix Material Grades: Using a slightly different but compatible alloy for the nut and bolt can reduce the tendency for the materials to weld together.

Torque

Torque is the rotational force applied to a fastener, such as a nut or bolt head, to tighten it. It is the input energy used to stretch the bolt and create the desired clamp load (tension). Technicians measure torque in units like foot-pounds (ft-lbs) or Newton-meters (N-m). While torque is easy to measure with a torque wrench, it is not a direct measurement of bolt tension. Friction at the threads and bearing surfaces consumes a large portion of the applied torque.

Torque Wrench

A torque wrench is a calibration tool technicians use to apply a precise amount of rotational force, or torque, to a fastener. This tool allows for controlled tightening, which is a critical step in achieving the target bolt tension. Torque wrenches come in various types, including click-type, beam, and digital models. Each provides a way to measure the applied torque.

Important Note: A torque wrench measures the input force (torque), not the resulting clamp load (tension). Factors like friction can significantly affect the final tension. Therefore, using a torque wrench is just one part of a comprehensive, controlled bolting procedure.

Toughness

Material toughness is a material’s ability to absorb energy and resist fracturing, especially under sudden impact. This property is critical for fasteners used in low-temperature service, where some materials can become brittle and fail unexpectedly. The Charpy impact test is a globally recognized method for measuring this toughness. The test determines the total energy a material absorbs during fracture.

The ASTM A320 specification, engineered for low-temperature performance, requires this testing for most fastener grades to ensure they remain ductile in cold environments. Testing temperatures must align with the actual service conditions. For example, ASTM standards define zones based on the minimum service temperature a structural member will experience.

| Temperature Zone | Minimum Service Temperature Range |

|---|---|

| Zone 1 | 0°F and above |

| Zone 2 | below 0°F to -30°F |

| Zone 3 | below -30°F to -60°F |

Selecting a bolt material with proven toughness for its specific temperature zone is essential for preventing brittle failure and ensuring joint safety.

Washer

A washer is a thin, disk-shaped plate with a hole in the middle. Technicians place it between a fastener’s head or nut and the mating surface. Washers serve several key functions in a bolted joint. They distribute the clamp load over a wider area, protect the flange surface from damage during tightening, and can provide a locking mechanism.

Flat Washer

A flat washer is the most common type of washer. Its primary function is to increase the bearing surface area under a nut or bolt head. This distribution of pressure helps prevent the fastener from digging into and damaging the surface of the clamped material, which is especially important when using softer materials.

Hardened Washer

A hardened washer is a flat washer that has been heat-treated to increase its hardness and strength. Technicians use it with high-strength bolts to provide a smooth, consistent, and durable bearing surface. This heat treatment serves two critical purposes:

- It prevents galling between the nut and the washer.

- It ensures the nut does not deform the washer or the flange surface, which helps achieve a more accurate and reliable preload.

Lock Washer

A lock washer is designed to prevent a nut or bolt from loosening due to vibration or dynamic loads. These washers create tension against the fastener. Common types, like split-ring or toothed washers, work by biting into the nut and the joint surface. This action increases resistance to rotation, helping to keep the connection secure.

Yield Strength

Yield strength is a fundamental mechanical property of a material. It defines the amount of stress at which the material begins to deform permanently. Before reaching its yield strength, a bolt under tension will stretch elastically. This means it behaves like a very stiff spring and will return to its original length if the load is removed. This elastic stretch is what creates the clamp load in a bolted joint.

However, if the applied load causes the stress in the bolt to exceed its yield strength, the material enters the plastic deformation range. The bolt will stretch permanently and will not return to its original dimensions. This permanent elongation is called yielding.

The Importance of the Elastic Range Engineers design bolted connections to operate well below the bolt’s yield strength. The goal is to stretch the bolt enough to create the necessary clamping force but keep it within its elastic region. This ensures the bolt can maintain a consistent preload over time. A yielded bolt has lost its “springiness” and can no longer hold the joint together effectively.

Yield strength is a critical value for ensuring the safety and reliability of a fastener. It represents the practical limit of a bolt’s useful strength. Exceeding this limit is considered a failure, even though the bolt has not yet broken.

Engineers often compare yield strength with other strength-related terms. The table below clarifies these key distinctions.

| Property | Definition | Nature | Purpose in Bolting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yield Strength | The stress at which a material starts to deform permanently. | An inherent material property. | A critical design limit to prevent permanent damage to the fastener. |

| Tensile Strength | The maximum stress a material can withstand before it breaks. | An inherent material property. | Represents the ultimate failure point of the bolt. |

| Proof Load | A specific test load a fastener must withstand without permanent deformation. | A quality control test value. | Verifies that a finished bolt meets its specified strength requirements. |

Selecting a bolt with the appropriate yield strength is essential. The chosen material must provide a sufficient safety margin above the required preload to account for any potential over-tightening or unexpected service loads. This careful selection prevents fastener failure and ensures the long-term integrity of the bolted connection.

This glossary provides a foundational understanding of fastener terminology. A solid grasp of these terms helps professionals achieve several key goals.

- It ensures clearer communication and more accurate project specifications.

- It leads to the assembly of safer and more reliable bolted connections.

Technicians, engineers, and procurement specialists should bookmark this guide. It serves as an invaluable reference for future projects and procurement tasks, promoting precision and safety in every application.

FAQ

Why is bolt lubrication critical?

Lubrication reduces friction during the tightening process. This action converts more applied torque into useful clamp load. It helps technicians achieve the correct preload accurately, which is essential for preventing joint leaks and ensuring fastener integrity.

What is the main difference between a bolt and a stud bolt?

A bolt has a pre-formed head on one end and threads on the other. A stud bolt is a headless rod with threads on both ends. Technicians use stud bolts with two nuts, a common configuration for joining two flanges.

How do engineers select the correct bolt grade?

Engineers choose a bolt grade based on the system’s pressure, temperature, and service environment. The selected grade’s specified tensile strength and material composition must safely handle the application’s maximum operational loads to ensure joint safety.

What are the primary causes of bolt failure?

Common causes include improper preload from incorrect tightening, fatigue from cyclic loads, and corrosion from environmental exposure. Hydrogen embrittlement can also cause sudden failure in high-strength steels under specific conditions.

Why use a heavy hex bolt over a standard hex bolt?

Heavy hex bolts feature a larger head and greater thickness. This design provides a wider bearing surface to distribute the clamp load more effectively. It also offers higher strength, making it the standard for high-pressure structural applications.

Can technicians reuse flange bolts?

Most industry standards advise against reusing flange bolts, especially in critical service. The initial tightening process can stretch a bolt or damage its threads. Using new fasteners ensures predictable performance and reliable joint integrity.

What is the primary purpose of a washer?

A washer distributes the fastener’s clamp load over a wider area. This action protects the flange surface from damage during tightening. Hardened washers also provide a smooth, consistent surface that helps achieve a more accurate preload.