An understanding of hex bolt terms is crucial for professionals in construction, manufacturing, and engineering. This comprehensive glossary provides clear definitions for the essential specifications associated with the hex bolt. It enables users to select the correct fastener for any application, from standard bolt casting to specialized custom fasteners. The global industrial fasteners market, which includes the hex bolt, is substantial and growing.

Market Insight 💡 The industrial fasteners market was valued at USD 124.2 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach USD 173.8 billion by 2034. This reflects the integral role of components like the hex bolt in global industries. A knowledgeable custom fasteners manufacturer can help navigate the complexities of this expanding market.

Mastering this terminology ensures every bolt and fastener connection is secure and reliable.

The Anatomy of a Hex Bolt

Understanding the individual components of a hex bolt is the first step toward selecting the correct fastener for your project. Each part has a specific name and function that contributes to the bolt’s overall performance.

The Head

The head is the part of the bolt that provides a surface for a wrench or socket to apply torque.

Hex Head

The Hex Head is the most common feature of this fastener. Its six-sided, hexagonal shape allows for reliable and efficient wrenching from multiple angles.

Indented Hexagon

An Indented Hexagon is a depression on the top of the hex head. This feature is a result of the cold forming manufacturing process and often contains manufacturer identification marks.

Flange

A Flange is a built-in washer under the head. This design distributes the clamping force over a wider area, eliminating the need for a separate washer.

Bearing Surface

The Bearing Surface is the flat area underneath the head (or flange) that makes direct contact with the mating surface. A smooth, flat bearing surface ensures even load distribution.

Wrenching Height

Wrenching Height refers to the thickness of the hex head. It determines the amount of surface area available for a tool to grip during installation and removal.

The Body (Shank)

The body, or shank, is the cylindrical portion of the bolt extending from beneath the head to the start of the threads.

Shank

The Shank is the smooth, unthreaded part of the bolt. Its primary function is to locate the fastener and resist shear forces.

Grip Length

Grip Length is the length of the unthreaded shank. Proper grip length is critical in shear-loaded joints, as it ensures the smooth shank, not the weaker threads, bears the sideways force. This positioning prevents stress concentration near the thread and enhances joint integrity.

Pro Tip 💡 A longer grip length allows the bolt to stretch elastically, like a spring. This elasticity helps maintain consistent clamp force under varying loads, improving the fastener’s fatigue resistance.

Body Diameter

The Body Diameter is the diameter of the shank. This dimension is typically equal to the nominal or major diameter of the thread.

The Threads

Threads are the helical ridges that allow the bolt to engage with a nut or a tapped hole, creating the clamping force.

Threads

Threads are the helical grooves on the end of the bolt. They convert the rotational force (torque) applied to the head into linear force (clamp load).

Thread Length

Thread Length measures the portion of the bolt that contains threads. This length must be sufficient to properly engage the nut or tapped hole.

Thread Pitch

Thread Pitch is the distance between adjacent threads. It is measured in threads per inch (TPI) for inch-series fasteners or in millimeters for metric fasteners.

Coarse Thread (UNC)

Coarse Thread (UNC), or Unified National Coarse, features a larger pitch and deeper thread profile. Engineers often prefer UNC threads in general construction and heavy machinery for several reasons:

- They assemble more quickly.

- They are more tolerant of dirty or damaged threads.

- They have greater resistance to stripping and cross-threading.

- Coating and plating processes are simpler to apply.

Fine Thread (UNF)

Fine Thread (UNF), or Unified National Fine, has a smaller pitch and more threads per inch. These fasteners offer higher tensile strength and are less likely to loosen under vibration, making them suitable for precision applications.

Thread Dimensions

Precise thread dimensions are essential for ensuring a proper fit between a bolt and a nut. These measurements define the geometry of the thread and are governed by strict industry standards.

Major Diameter

The Major Diameter is the largest diameter of a screw thread, measured from the crest (the outermost point) of the thread on one side to the crest on the opposite side. This is typically the same as the nominal size of the bolt.

Minor Diameter

The Minor Diameter is the smallest diameter of a screw thread. This dimension is measured from the root (the innermost point) of the thread on one side to the root on the other. It defines the solid core of the fastener.

Pitch Diameter

The Pitch Diameter is the diameter of an imaginary cylinder that passes through the threads at a point where the width of the thread and the space between threads are equal. It is a critical dimension for controlling the fit of a screw thread. The average of the major and minor diameters provides a close approximation of the pitch diameter. For metric threads, it can be calculated with high precision.

Technical Calculation ⚙️ The pitch diameter (Dp) for an external metric thread is calculated using its relationship to the major diameter (Dmaj) and the thread pitch (P). The formula is:

Dp ≈ Dmaj − 0.649519 ⋅ P

The Point

The point is the very end of the bolt, designed to facilitate easy entry into a nut or tapped hole. The design of the point varies based on the intended application.

Chamfer Point

A Chamfer Point is the standard point style for a typical hex bolt. It features a beveled or angled end, which removes the first partial thread. This design serves a primary purpose:

- It guides the hex bolt smoothly into a pre-drilled or tapped hole.

- It prevents damage to the leading thread during initial engagement.

Gimlet Point

A Gimlet Point is a tapered, threaded point most commonly found on lag bolts designed for use in wood. Unlike a chamfer point, a gimlet point is functional and aggressive.

- It is designed to displace material, effectively drilling its own pilot hole as it is driven.

- This feature allows for faster installation in softer materials without the need for a separate pre-drilled hole.

Key Mechanical Properties and Strength Grades

The performance of a hex bolt depends on its mechanical properties. These characteristics define how the fastener will behave under stress and determine its suitability for a specific application. Strength grades provide a standardized system for classifying a bolt based on these critical properties.

Fundamental Strength Terms

These terms quantify a fastener’s ability to resist different types of forces.

Tensile Strength

Tensile Strength is the maximum pulling or stretching stress a material can withstand before it fractures. This property represents the ultimate load-bearing capacity of the fastener. For example, standard hex bolts typically offer a tensile strength around 400 MPa, while heavy hex bolts used in structural projects can exceed 600 MPa.

Yield Strength

Yield Strength defines the stress point at which a material begins to deform permanently. Before reaching this point, a bolt will return to its original shape once the load is removed. Exceeding yield strength causes permanent stretching.

Proof Load

Proof Load is the maximum force a fastener can endure without any permanent deformation. Manufacturers use this as a quality control measure. A bolt that passes a proof load test is certified to handle a specific load safely in its application.

Shear Strength

Shear Strength measures a bolt’s capacity to resist forces applied perpendicular to its longitudinal axis. This is the force that would attempt to slice the bolt in half.

Material Behavior

These properties describe how a bolt’s material responds to applied forces.

Hardness

Hardness refers to a material’s ability to resist surface indentation, scratching, and wear. A harder material is generally more durable against surface damage.

Ductility

Ductility is a measure of a material’s ability to stretch or deform under tensile stress before it breaks. Some advanced steel fasteners exhibit high ductility, with elongation after fracture exceeding 50%. This allows them to absorb significant energy before failure.

Elasticity

Elasticity is the material’s ability to return to its original dimensions after an applied load is removed. This behavior only occurs when the stress is below the material’s yield strength.

Elongation

Elongation quantifies ductility by measuring how much a bolt stretches as a percentage of its original length before it fractures. Higher elongation indicates greater ductility.

SAE Grade Markings (Inch System)

The Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) provides a common grading system for inch-series fasteners, indicating their strength level.

Quick Guide: SAE Grades ⚙️ Higher grade numbers correspond to increased material strength.

- Grade 2: Low strength for general-purpose, light-duty use.

- Grade 5: Medium strength, common in automotive and construction.

- Grade 8: High strength for critical, high-stress applications.

Grade 2

Grade 2 bolts are made from low-carbon steel. They are the most common commercial grade and are suitable for applications with low stress and light loads.

Grade 5

Grade 5 bolts are made from medium-carbon steel that is quenched and tempered for increased strength. They are a popular choice for automotive and machinery applications.

Grade 8

Grade 8 bolts are made from a medium-carbon alloy steel. They are also quenched and tempered to achieve a higher tensile strength than Grade 5, making them ideal for high-stress environments.

Grade Markings

SAE grades are easily identified by the markings on the head of the hex bolt.

- Grade 2: No markings.

- Grade 5: Three radial lines.

- Grade 8: Six radial lines.

ISO Property Classes (Metric System)

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) provides a system for grading metric fasteners. This system, defined by ISO 898-1, uses a numerical “property class” to indicate the mechanical strength of a hex bolt. The numbers directly relate to the fastener’s tensile and yield strengths, offering a precise method for specification. A higher class number signifies a stronger fastener capable of handling greater loads. This classification is essential for engineers and manufacturers working with metric specifications worldwide.

Understanding the Numbers ⚙️ The property class consists of two numbers separated by a decimal point (e.g., 8.8).

- The first number (8) represents 1/100th of the nominal tensile strength in megapascals (MPa). So, 8 x 100 = 800 MPa.

- The second number (8) indicates that the yield strength is 80% of the tensile strength. So, 0.80 x 800 MPa = 640 MPa.

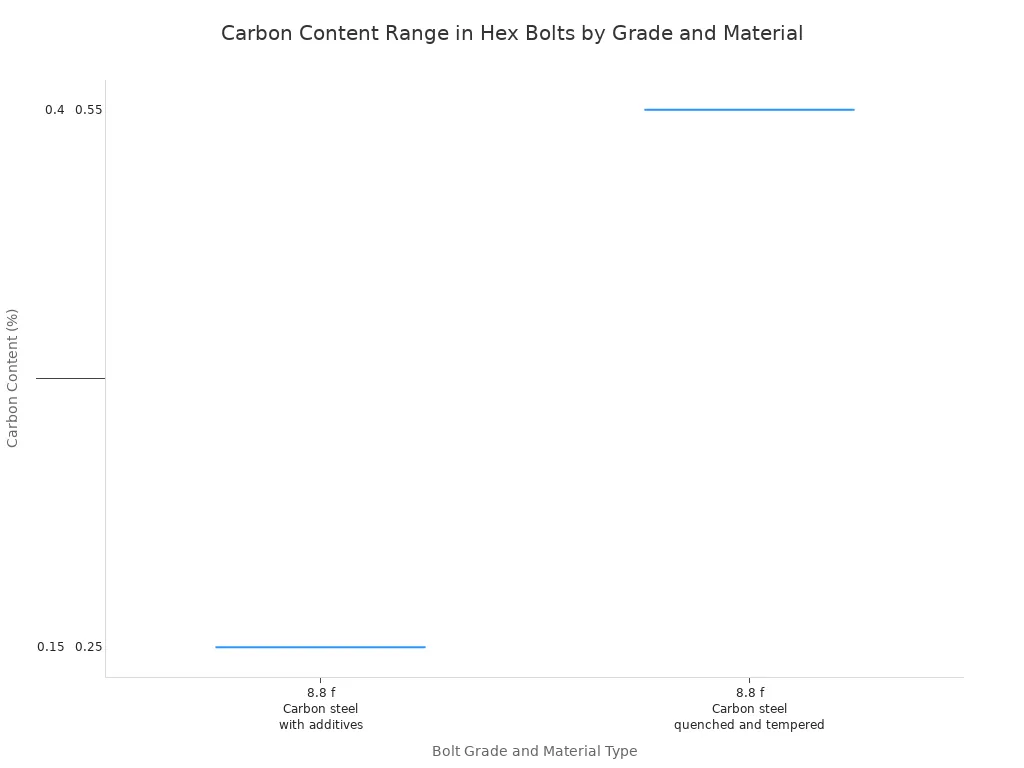

Class 8.8

Class 8.8 bolts are the most common class of high-tensile fasteners. They are manufactured from medium carbon steel that is quenched and tempered. This process gives them good tensile strength and toughness. Their strength is roughly comparable to the imperial SAE Grade 5. Engineers frequently specify this bolt for automotive assemblies, machinery, and general construction where moderate to high strength is necessary.

Class 10.9

Class 10.9 fasteners offer superior strength for more demanding applications. Made from quenched and tempered alloy steel, they provide a higher tensile and yield strength than Class 8.8. This makes them suitable for high-stress situations, such as engine components, structural steel connections, and heavy equipment assembly. Their performance is similar to that of an SAE Grade 8 fastener.

Class 12.9

Class 12.9 represents one of the highest standard strength classes for metric fasteners. These bolts are made from a high-grade alloy steel that is quenched and tempered to achieve extreme tensile strength. Their exceptional load-bearing capacity makes them the top choice for critical applications. Industries use them in performance racing, heavy machinery pivots, and safety-critical structural joints where failure is not an option.

Property Class Markings

Identifying the property class of a metric hex fastener is straightforward. The numerical class designation is stamped directly onto the head of the fastener, often along with the manufacturer’s identification mark.

- Class 8.8: The head is marked with “8.8”.

- Class 10.9: The head is marked with “10.9”.

- Class 12.9: The head is marked with “12.9”.

This clear labeling system eliminates guesswork and ensures the correct fastener is used for the application, guaranteeing safety and performance.

Common Materials for Hex Bolts

The material of a hex bolt dictates its strength, corrosion resistance, and suitability for specific environments. Manufacturers most commonly use carbon steel and stainless steel for their affordability and durability. However, specialized applications demand materials with unique properties, from high-temperature alloys to lightweight non-ferrous metals.

Steel-Based Materials

Steel, an alloy of iron and carbon, is the foundation for the most common and strongest fasteners. The specific composition and treatment of the steel determine the fastener’s final mechanical properties.

Carbon Steel

Carbon steel is a fundamental material for bolt manufacturing. Its properties are directly influenced by its carbon content; increasing the carbon makes the steel harder and stronger but reduces its ductility. This material is the basis for many common high-tensile strength grades used in structural joints and heavy machinery.

Alloy Steel

Alloy steel is carbon steel enhanced with additional elements like chromium, manganese, or molybdenum. These alloys improve specific properties such as hardenability, wear resistance, and high-temperature strength. This makes alloy steel the ideal choice for the most demanding hex fastener applications, including engine components and high-stress machinery.

Quenched and Tempered Steel

Quenching and tempering is not a material itself but a critical heat treatment process. Manufacturers apply it to medium or high-carbon and alloy steels. The process involves heating the steel, rapidly cooling (quenching) it to create hardness, and then reheating it to a lower temperature (tempering) to increase toughness. This treatment produces high-strength grades like Class 10.9 and 12.9.

Stainless Steel

Stainless steel is an iron-based alloy containing a minimum of 10.5% chromium, which creates a passive, corrosion-resistant surface layer. This makes it a top choice for applications exposed to moisture and corrosive elements.

Stainless Steel

The term “stainless steel” covers a wide family of corrosion-resistant steel alloys. Their primary benefit is longevity in environments where a standard carbon steel fastener would rust and fail. They are essential in everything from home fittings to solar panel structures.

18-8 Stainless Steel

This common stainless steel grade contains approximately 18% chromium and 8% nickel. It offers good general corrosion resistance and is widely used in various applications. However, it is susceptible to corrosion in chloride-rich environments like coastal areas.

316 Stainless Steel

For superior corrosion resistance, engineers specify 316 stainless steel. The addition of molybdenum gives it exceptional protection against chlorides and other harsh chemicals.

| Feature | 18-8 (304) Stainless Steel | 316 Stainless Steel |

|---|---|---|

| Composition | 18-20% Chromium, 8-10.5% Nickel | 16-18% Chromium, 10-14% Nickel, 2-3% Molybdenum |

| Corrosion Resistance | Good general resistance; less resistant to chlorides. | Exceptional resistance to chlorides and chemicals. |

| Marine Environment | Suitable for less aggressive areas; can corrode. | Ideal for marine applications (ships, docks). |

Non-Ferrous Materials

Non-ferrous materials lack significant amounts of iron, giving them unique properties like high conductivity, non-magnetic behavior, and excellent corrosion resistance.

Silicon Bronze

Silicon bronze is a copper alloy known for its superior corrosion resistance, especially in marine environments. It is frequently used for marine deck hardware and electrical power distribution systems.

Brass

Brass, an alloy of copper and zinc, is valued for its decorative appearance and good electrical conductivity. Its applications often include electrical panel assemblies and aesthetic fittings in furniture.

Aluminum

Aluminum alloys provide a good strength-to-weight ratio, making them ideal where minimizing weight is critical. The aerospace industry heavily relies on aluminum for structural connections and other components.

A Glossary of Finishes and Protective Coatings

A protective finish is a critical feature of a hex bolt. It shields the fastener from corrosion, wear, and environmental damage. This part of the glossary details the most common coatings and treatments available.

Zinc Coatings

Zinc coatings provide sacrificial protection. The zinc corrodes before the underlying steel, extending the life of the fastener.

Zinc Plating

Zinc plating, or electroplating, is a process where manufacturers apply a thin layer of zinc to a steel hex bolt using an electrical current. This finish offers a baseline level of corrosion resistance and a clean, bright appearance.

Yellow Zinc Chromate

This finish involves applying a yellow chromate conversion coating over standard zinc plating. The chromate layer provides additional corrosion resistance compared to clear zinc and gives the fastener its characteristic yellowish-gold color.

Clear Zinc Chromate

Clear zinc chromate is a post-plating treatment that provides corrosion protection while maintaining a bright, silver-like appearance. The primary difference between clear and yellow zinc is the chromate pigment, not the coating thickness. Both types can have identical minimum thicknesses under various ASTM specifications.

Galvanization

Galvanization applies a much thicker layer of zinc than standard plating, offering superior protection for harsh environments.

Hot-Dip Galvanized (HDG)

Hot-dip galvanization involves immersing the fastener in a bath of molten zinc. This process creates a thick, durable, and metallurgically bonded alloy coating.

- Physical Barrier: The thick zinc layer offers excellent, long-term corrosion resistance.

- Mechanical Damage: It provides some defense against abrasion and impact.

- Applications: This finish is ideal for outdoor construction and marine environments.

Mechanical Galvanized

Mechanical galvanizing is a cold process. Manufacturers tumble fasteners in a drum with zinc powder, glass beads, and proprietary chemicals. The tumbling action cold-welds the zinc onto the fastener’s surface, creating a uniform coating without the risk of hydrogen embrittlement.

Other Finishes and Treatments

Beyond zinc, a variety of specialized finishes offer unique protective and aesthetic properties.

Phosphate and Oil

This finish is a chemical conversion process that creates a thin, crystalline phosphate layer on the steel surface. A subsequent oil coating enhances corrosion resistance. It typically results in a matte gray or black appearance.

Black Oxide

Black oxide is a conversion coating that produces a deep black finish. It offers mild corrosion resistance and is often oiled to improve its protective qualities. Its primary benefit is maintaining the fastener’s dimensional integrity.

Passivation

Passivation is a chemical treatment specifically for stainless steel. The process removes free iron from the surface and enhances the natural chromium-oxide layer, maximizing the material’s inherent corrosion resistance.

Dacromet

Dacromet is a water-based coating containing zinc and aluminum flakes. This composite, multilayered structure offers excellent corrosion and heat resistance. It is applied as a liquid and then heat-cured.

Geomet

Geomet is an environmentally friendly, chrome-free alternative to Dacromet. It consists of zinc and aluminum flakes in a water-based binder, providing exceptional corrosion protection, especially in salt-laden environments.

| Coating Type | Salt Spray Resistance (No Red Rust) |

|---|---|

| Dacromet | ≥ 480 hours |

| GEOMET | ≥ 720–1200 hours |

Testing Note 📝 Salt spray tests primarily simulate chloride-driven corrosion. They provide comparative data but do not perfectly predict real-world durability. For more accurate life predictions, engineers often recommend cyclic corrosion tests or outdoor exposure testing.

Manufacturing Processes and Bolt Types

The way a hex bolt is manufactured directly impacts its performance and strength. Manufacturers use specific formation and threading methods to produce different types of fasteners for various applications. Understanding these processes helps in selecting the right fastener for the job.

Bolt Formation Methods

The initial shaping of the bolt’s head and shank is done through one of two primary methods: cold forming or hot forging.

Cold Forming (Cold Heading)

Cold forming is a high-speed manufacturing process performed at room temperature. A wire or rod is cut to length and then forced into a series of dies to form the head and shank. This process work-hardens the material, significantly increasing its tensile and yield strength.

Hot Forging

Hot forging involves heating the steel above its recrystallization temperature before shaping it with hammers or presses. This method refines the material’s grain structure, resulting in high toughness and excellent impact strength. High strength is achieved through subsequent heat treatment rather than the forging process itself.

| Feature / Process | Cold Forging (Cold Heading) | Hot Forging |

|---|---|---|

| Grain Structure | Continuous grain flow aligned with part geometry. | Refined, equiaxed grain structure. |

| Strength | Significantly increased due to work hardening. | Strength is achieved via subsequent heat treatment. |

| Fatigue Performance | Excellent due to continuous grain flow. | Moderate; depends on finishing steps. |

| Toughness | Good, with adequate ductility. | High toughness and excellent impact strength. |

Thread Creation Methods

After the bolt is formed, the thread must be created. The two main methods produce threads with very different performance characteristics.

Rolled Threads

Rolled threads are formed using a cold-working process. The blank fastener is pressed and rolled between dies, which displaces the material to form the thread. This method does not remove any material. Instead, it reforms the steel’s natural grain structure, making the thread inherently stronger. The burnishing effect creates a smoother surface, improving resistance to galling and damage during handling. This process results in superior fatigue life, which is why industries like automotive exclusively use rolled threads for critical components.

Cut Threads

Cut threads are produced by a machining process that removes material from the bolt blank to create the thread profile. This cutting action interrupts the steel’s grain flow, which can create stress points and reduce the thread’s structural integrity compared to a rolled thread.

Common Hex Bolt Variations

While many types of hex fasteners exist, a few common variations serve distinct purposes.

Hex Cap Screw

A hex cap screw is a precision fastener with a washer face on the bearing surface and tighter tolerances than a standard hex bolt. It is engineered for precise torque application, with a head designed to distribute force effectively and minimize stripping.

Tap Bolt

A tap bolt is defined by its fully threaded shank. These types are designed for use in a hole that has been tapped (threaded) all the way through.

- They are ideal for fastening materials of various thicknesses.

- The fully threaded design provides versatility for many repair and maintenance tasks.

- They can be mated with an internally threaded hole or used with a nut.

High Strength Bolt

A high strength bolt is a fastener made from medium carbon alloy steel that has been quenched and tempered. These bolts, such as SAE Grade 8 or ISO Class 10.9 and 12.9, are designed for critical structural connections and high-stress applications where joint failure is not an option.

Essential Hex Bolt Terms for Standards and Fit

Standardization ensures that a hex bolt from one manufacturer will fit correctly with a nut from another. Governing bodies establish these rules, defining everything from material strength to the precise dimensions of a thread. Understanding these essential hex bolt terms guarantees interchangeability, safety, and performance in any assembly.

Governing Standards Bodies

Several organizations develop and publish the standards that regulate fastener manufacturing and performance. Each body often has a specific area of focus.

ASTM (American Society for Testing and Materials)

ASTM International creates technical standards for materials and products. In the fastener industry, ASTM standards often focus on construction and industrial applications. For example, the ASTM A307 specification covers low-carbon steel bolts and studs for general-purpose use, such as light construction and securing HVAC components. Grade A307B is a low-strength heavy hex bolt specifically designed for cast iron pipe flange connections.

SAE (Society of Automotive Engineers)

SAE standards are tailored for the mobility sector, including automotive and aerospace applications. These standards prioritize performance metrics like strength and durability. The SAE J429 specification, for instance, defines the grades for inch-series fasteners, which are identified by radial lines on the bolt head.

ISO (International Organization for Standardization)

ISO aims to harmonize specifications globally to facilitate international trade and ensure product compatibility. The ISO 898-1 standard is the primary specification for metric fasteners made from carbon and alloy steel. It establishes property classes that clearly define a fastener’s mechanical properties.

DIN (German Institute for Standardization)

DIN is the German national organization for standardization. Many DIN standards for fasteners have been influential worldwide and are still referenced, though many are being superseded by ISO standards.

IFI (Industrial Fasteners Institute)

The IFI is a North American trade association that compiles and publishes fastener standards. It serves as a critical resource, consolidating specifications from bodies like ASTM, SAE, and ISO into a comprehensive guide for manufacturers and engineers.

Dimensional Specifications and Fit

These hex bolt terms define the physical size of a fastener and how tightly it will engage with a nut or tapped hole.

Nominal Size

The Nominal Size is the designation used for general identification. It typically refers to the major diameter of the thread. For example, a “1/2-inch” bolt has a nominal size of 1/2 inch.

Tolerance

Tolerance is the permissible amount of variation in a dimension. No part can be manufactured to an exact size, so tolerance defines an acceptable range. Tighter tolerances result in a more precise but more expensive fastener.

Thread Class (1A, 2A, 3A)

Thread class defines the tolerance and allowance of a thread, determining how loose or tight the fit will be. The “A” designates an external thread (for a bolt), while “B” denotes an internal thread (for a nut).

| Thread Class | Tolerance & Fit | Common Application |

|---|---|---|

| 1A | Loose fit with the largest tolerance. | Allows for quick and easy assembly, even in dirty conditions. |

| 2A | Standard fit with a moderate tolerance. | The most common class for commercial and industrial fasteners. |

| 3A | Tight fit with a close tolerance and no allowance. | Used in high-precision applications where accuracy is critical. |

Application and Installation Terminology

Proper installation is as critical as selecting the right hex bolt. Understanding the key concepts of fastening and the potential failure modes ensures that a joint performs safely and effectively throughout its service life. This terminology covers the essential principles of bringing and keeping parts together.

Fastening Concepts

These concepts describe the forces at play when tightening a fastener.

Torque

Torque is the rotational force applied to the head of a hex bolt during installation. This turning effort is what creates the tension that holds a joint together. Engineers use a fundamental formula to determine the correct torque: T = K × F × D. In this equation, ‘T’ is the torque, ‘K’ is the nut factor, ‘F’ is the target clamp load, and ‘D’ is the bolt diameter. The K-factor is a crucial variable that accounts for friction between the threads, material types, and any coatings present.

Clamp Load (Preload)

Clamp load, also known as preload, is the tension or stretching force created in a fastener when it is tightened. This internal force acts like a powerful spring, clamping the joint components together. A sufficient clamp load is essential for a joint to resist external forces and prevent loosening under vibration.

Torque-to-Yield

Torque-to-yield is an advanced tightening method where a fastener is intentionally tightened beyond its elastic limit into its plastic region. This technique achieves the maximum possible clamp load from the fastener, creating a very secure and permanent joint. It is often used in critical automotive applications like engine head bolts.

Torsion

Torsion is the twisting stress that develops along the shank of a bolt as torque is applied to the head. It is a byproduct of overcoming friction in the threads and under the head. A significant portion of the input torque is consumed by torsion, not by creating useful clamp load.

Common Failure Modes

Recognizing common failure modes helps engineers and technicians prevent them through proper design and installation practices.

Galling (Thread Seizing)

Galling, or cold welding, is a severe form of adhesive wear. It occurs when pressure and friction cause mating threads to seize, a problem often seen with stainless steel fasteners.

- Cause: High friction and pressure, often from over-tightening without lubrication.

- Prevention: Using lubricants, applying correct torque, and ensuring proper thread alignment can prevent this issue.

Hydrogen Embrittlement

Hydrogen embrittlement makes high-strength steel brittle and susceptible to sudden, delayed failure. Hydrogen atoms can be absorbed during manufacturing processes like electroplating. This makes the fastener lose its ductility, leading to catastrophic fracture under load without warning. Proper material selection and controlled manufacturing processes are key to prevention.

Fatigue Failure

Fatigue failure is the result of repeated cyclic loading. Microscopic cracks form and grow over time, eventually causing the hex fastener to snap unexpectedly.

- Cause: Dynamic loads and insufficient clamp load (preload).

- Prevention: Ensuring a correct and consistent preload is the best defense. This keeps the joint tight and minimizes stress fluctuations in the bolt.

Over-Torquing

Over-torquing occurs when excessive torque is applied, stressing the fastener beyond its yield strength. This can cause the fastener to fracture immediately during installation or leave it permanently stretched and weakened, compromising the joint’s integrity and long-term reliability.

Mastering hex bolt terms is critical for ensuring project safety and durability. This glossary serves as a reliable reference, enabling professionals to specify the correct fastener. Improper fastener selection, such as using a bolt weakened by poor processing, leads to failure. It is essential to align the fastener grade, material, and finish with the application’s needs. Verifying each hex fastener and bolt through markings and certificates ensures the integrity of all fasteners. A deep understanding of hex bolt terms prevents costly errors.

FAQ

What is the difference between a hex bolt and a hex cap screw?

A hex cap screw has tighter manufacturing tolerances than a standard hex bolt. It also features a washer face under the head. This design provides a more precise fit and better load distribution, making it ideal for applications requiring accurate torque.

Can high-strength bolts be reused?

Engineers generally advise against reusing high-strength bolts, especially those tightened to yield. The initial tightening process can permanently stretch the fastener. Reusing a stretched bolt compromises its clamping force and increases the risk of failure under load.

Why is lubrication important for fasteners?

Lubrication reduces friction between mating threads and under the bolt head. This allows a greater percentage of the applied torque to convert into useful clamp load. It also helps prevent galling, particularly with stainless steel fasteners, ensuring consistent and reliable installation.

What does “fully threaded” mean for a hex bolt?

A fully threaded bolt, known as a tap bolt, has threads running along its entire shank. This design offers maximum engagement in tapped holes or with nuts. It provides versatility for clamping materials of various thicknesses where shear strength is less critical.

How do you choose between coarse (UNC) and fine (UNF) threads?

The choice depends on the application’s demands.

- UNC (Coarse): Best for rapid assembly and general use. They are more tolerant of damage.

- UNF (Fine): Better for precision tasks. They offer higher tensile strength and resist loosening from vibration.

What happens if the wrong torque is applied?

Applying incorrect torque compromises joint integrity.

Under-torquing results in low clamp load, leading to loosening or fatigue failure. Over-torquing can stretch the bolt past its yield point or cause it to fracture, resulting in immediate joint failure.