Properly installing hex bolts is critical for structural safety. A custom fasteners manufacturer ensures quality through processes like bolt casting. Installers must select the correct hex bolt grade for specific load requirements. Proper installation begins with clean and aligned connection surfaces. Applying precise torque achieves the necessary clamping force for structural integrity.

Note: Research shows that nearly 30% of construction-related failures stem from deficiencies in anchor bolt installations, highlighting the severe risks of improper techniques. A reliable source for custom fasteners is essential.

Understanding Hex Bolt Specifications

Selecting the correct hex bolt is the first critical step toward a secure structural connection. A bolt’s markings, material, and thread design dictate its strength, corrosion resistance, and application. Misinterpreting these specifications can compromise the integrity of the entire assembly. This section breaks down the essential details every installer must know.

Decoding Bolt Grades and ASTM Standards

Bolt grades define the mechanical properties of a fastener, primarily its tensile strength. The American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) sets these standards for construction. ASTM F3125 is now the primary specification for high-strength structural bolts. It unifies six previous standards, including the widely known A325 and A490, which are now considered grades within the F3125 framework.

Differentiating A325 and A490 High-Strength Bolts

ASTM F3125 Grade A325 and Grade A490 bolts are the workhorses of structural steel connections, but they serve different purposes.

- Grade A325 bolts have a minimum tensile strength of 120 ksi (kips per square inch). They are common in buildings, bridges, and other structures.

- Grade A490 bolts offer a higher minimum tensile strength of 150 ksi. Installers use them for connections requiring greater strength or in designs with fewer bolts.

Important Note: While ASTM officially withdrew the standalone A325 and A490 standards in 2016, the industry still uses these terms to refer to the grades under the new ASTM F3125 specification. Bolt head markings remain the same to avoid confusion.

Understanding Grade 2, 5, and 8 Bolts

For non-structural or lower-stress applications, Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) grades are common. These are identified by radial lines on the bolt head.

- Grade 2: No head markings. This is a low-strength carbon steel bolt for general hardware use.

- Grade 5: Three radial lines. It is a medium-strength bolt, heat-treated for increased toughness.

- Grade 8: Six radial lines. This is a high-strength bolt, quenched and tempered for use in demanding applications like vehicle suspensions.

Matching Material to the Environment

A bolt’s material determines its resistance to corrosion and environmental stress. Choosing the wrong material can lead to premature failure, especially in harsh conditions.

When to Use Stainless Steel Bolts

Stainless steel bolts are ideal for environments with high moisture or exposure to corrosive agents. Their chromium content creates a passive, rust-resistant layer. They are essential in:

- Marine environments where saltwater and chlorides cause pitting and crevice corrosion.

- Chemical processing plants with exposure to acids and caustic solutions.

- Architectural applications where appearance and longevity are key.

The Role of Galvanized and Coated Bolts

Coatings provide a protective barrier for carbon steel bolts. The choice of coating depends on the severity of the environment.

| Coating Type | Corrosion Resistance | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Dip Galvanized | Excellent | Outdoor structures, utility poles, and industrial settings. |

| Zinc Plated | Good | Indoor or dry, light-duty applications. Not for outdoor exposure. |

| Ceramic Coated | Superior | Extreme environments like offshore platforms or chemical plants. |

Hot-dip galvanizing creates a thick, durable zinc layer that offers both barrier and cathodic protection, making it a standard for structural steel.

Choosing the Right Thread Type

The final specification to consider is the thread type, which affects a bolt’s resistance to loosening and its ease of installation.

Coarse Threads (UNC) for General Construction

Unified National Coarse (UNC) threads are the standard for most construction projects. Their deeper, wider threads are more tolerant of minor damage, resist stripping, and allow for faster installation. They are perfect for general assembly where speed is a factor.

Fine Threads (UNF) for Vibration Resistance

Unified National Fine (UNF) threads have a larger number of threads per inch. This provides greater tensile stress area and finer adjustment capability. Their primary advantage is superior resistance to loosening from vibration, making them suitable for machinery, engines, and applications subject to dynamic loads.

Selecting the Right Hex Bolt for the Job

After identifying the correct bolt grade and material, an installer must select the precise size and accompanying hardware. A bolt that is too short, too long, or paired with the wrong nut can fail under load. This step ensures every component of the bolted connection works together as a system.

Verifying Proper Bolt Diameter and Hole Size

The relationship between the bolt diameter and the hole size is fundamental to a connection’s strength. A proper fit distributes loads correctly and prevents premature failure.

Standard Hole vs. Oversized or Slotted Holes

Most structural connections use standard holes, which provide a snug fit. The American Institute of Steel Construction (AISC) specifies a small clearance to ease bolt entry. Oversized or slotted holes may be used for tolerance adjustments but often require plate washers to ensure proper bearing.

AISC Standard Hole Clearance The standard clearance depends on the bolt’s diameter. | Bolt Diameter | Standard Hole Clearance | | :— | :— | | Up to 7/8 inch | Bolt diameter + 1/16″ | | 1 inch and above | Bolt diameter + 1/8″ |

Ensuring Correct Fit to Prevent Shear

A loose fit increases the risk of bolt shear and reduces the connection’s bearing capacity. Research shows that as the ratio of hole diameter to the surrounding material width increases, the connection’s ultimate bearing strength declines significantly. This change concentrates stress around the hole, which can cause the connection to fail in tension or shear rather than bearing as designed.

Calculating Required Bolt Length

A bolt must be long enough to engage the nut fully but not so long that it interferes with other components. Proper length is key when installing hex bolts.

Understanding Grip Length

Grip length is the total thickness of all the material layers, including washers, that the bolt clamps together. Installers must measure this distance accurately to determine the required bolt length.

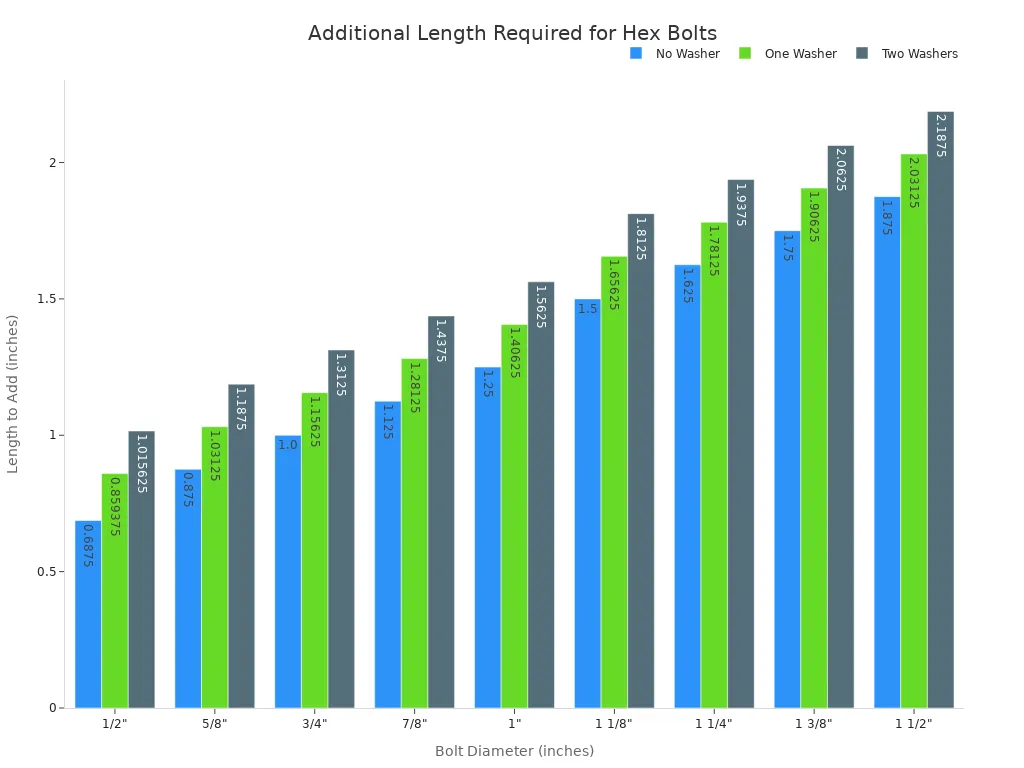

The “Two-Thread” Protrusion Rule

A correctly installed bolt should protrude through the nut by at least two full threads. This ensures full thread engagement and load-carrying capacity. To calculate the required length, add a specific value to the grip length based on the bolt diameter and number of washers.

Required Bolt Length = Grip Length + Length to Add

Matching Nuts and Washers to the Bolt

Bolts, nuts, and washers are engineered to work as a matched set. Using incompatible components is a critical safety error that can lead to connection failure.

Ensuring Nut Grade Compatibility

A nut must be strong enough to handle the tension generated by the bolt. Pairing a high-strength bolt like an ASTM A490 with a lower-grade nut can cause the nut’s threads to strip during tightening. Always use a nut with a grade equal to or greater than the bolt grade.

| Bolt Type (ASTM F3125) | Compatible Nut (ASTM A563) |

|---|---|

| Grade A325 (Type 1) | Grade C, D, DH |

| Grade A490 (Type 1) | Grade DH |

| Grade A490 (Type 3) | Grade DH3 |

Pro Tip: ASTM A194 Grade 2H nuts are a suitable and common substitute for A563 Grade DH nuts.

The Role of Hardened F436 Washers

Hardened washers, specified by ASTM F436, are essential in high-strength bolted connections. They prevent galling (surface damage) on the nut and joint surface during tightening. They also distribute the load over a larger area, which is critical for achieving proper tension.

When to Use Beveled Washers

Installers use beveled washers when a bolting surface is not perpendicular to the bolt’s axis. These washers are tapered to compensate for the slope on surfaces like I-beams or channels, ensuring the nut and bolt head have a flat, solid bearing surface.

Pre-Installation Best Practices

A successful connection depends on more than just the bolt itself. The condition of the steel surfaces and the alignment of the holes are just as critical. Following proper pre-installation procedures ensures that the bolted joint can achieve its designed strength and long-term performance.

Preparing and Aligning Connection Surfaces

The contact surfaces, or faying surfaces, must be properly prepared to ensure uniform clamping pressure and, in slip-critical connections, the required friction.

Cleaning Surfaces of Debris, Rust, and Mill Scale

All joint surfaces must be free of contaminants that could prevent solid contact. Installers should remove loose rust, dirt, and other debris. For heavy rust or the hard, flaky layer known as mill scale, several methods are effective:

- Mechanical Methods: Using angle grinders with flap discs, coarse wire wheels, or ceramic abrasives physically removes scale and rust.

- Chemical Methods: Applying solutions like muriatic or phosphoric acid can dissolve rust and scale, which installers then remove.

- Blasting: Sandblasting or media blasting is highly effective for creating a clean, uniformly textured surface.

Ensuring Surfaces are Flat and Free of Burrs

Surfaces must be flat to achieve full contact. Installers must grind down any burrs or high spots around the edges of bolt holes. For slip-critical connections, the surface condition is paramount. Paint is only allowed on faying surfaces if it is qualified for slip resistance.

Important RCSC Update: The Research Council on Structural Connections (RCSC) previously required wire brushing of hot-dip galvanized surfaces. This practice is now prohibited. Research confirms that as-galvanized surfaces provide adequate slip resistance without brushing.

Checking for Gaps Between Plies

Before installing hex bolts, installers must bring the steel plies into firm contact. Any gaps between the layers will prevent the bolt from achieving the correct clamping force, as the torque will be spent closing the gap instead of tensioning the bolt.

Aligning Bolt Holes Correctly

Forcing a bolt into a misaligned hole can damage threads and compromise the connection’s integrity.

Using Drifts or Spud Wrenches for Alignment

Installers use tapered tools like drift pins or the tapered end of a spud wrench to align bolt holes. They insert the pin and move it to bring the holes into alignment, creating a clear path for the bolt. This method prevents thread damage that can occur from hammering a bolt into place.

Starting Bolts by Hand to Prevent Cross-Threading

Installers should always start threading a bolt into a nut by hand for the first few turns. This provides tactile feedback and ensures the threads are properly engaged. Using an impact wrench to start a bolt can easily lead to cross-threading, which ruins both the bolt and the nut.

The Role of Lubrication

Lubrication is a critical component of high-strength bolting, as it helps regulate the relationship between torque and tension.

When and Why to Use an Approved Lubricant

A lubricant’s primary job is to reduce the friction between the nut and the bolt threads, as well as between the nut and the washer. Research shows that different lubricants, like ceramic pastes, create consistent friction. This consistency ensures that the installer’s applied torque reliably translates into bolt tension (clamp load) rather than being wasted overcoming unpredictable friction.

Applying Lubricant to Threads and Nut Face

High-strength bolts typically ship with a manufacturer-applied, wax-based lubricant. Studies confirm that applying lubricant to both the threads and the face of the nut (the underhead surface) is highly effective at reducing friction. Installers should keep fasteners in their protective packaging until use to preserve this coating.

Dangers of Using Unspecified Lubricants

Using the wrong lubricant—or relubricating bolts in the field—is a dangerous practice.

- Only the manufacturer should apply lubricant. RCSC guidelines state that inspectors should not authorize relubrication by anyone else.

- Unspecified lubricants can alter the torque-tension relationship, leading to inaccurate pre-tensioning.

- If a bolt’s factory lubrication is compromised by weather or excessive handling, the assembly must be re-tested or replaced.

The Installation Process: Tools and Techniques

Proper installation transforms a set of individual components into a robust, unified structural connection. This process demands precision, the correct equipment, and a systematic approach. Using the right tools and following established techniques ensures that each bolt achieves its specified tension, providing the clamping force necessary for structural integrity.

Using the Right Tools for the Job

Selecting the appropriate tool for each stage of the installation is not a matter of convenience; it is a requirement for safety and quality. Each tool has a specific function, from initial alignment to final tensioning.

Calibrated Torque Wrenches for Final Tightening

A calibrated torque wrench is a precision instrument designed to apply a specific amount of rotational force (torque) to a fastener. Installers use these tools for the final tightening stage when using the calibrated wrench method. Regular calibration is mandatory. A wrench that is out of calibration can lead to dangerously under-tightened or over-tightened bolts.

Impact Wrenches for Snugging

Impact wrenches deliver high torque and rapid rotational impacts, making them ideal for quickly drawing steel plies together. Their primary role is to bring a connection to the “snug-tight” condition. They are not precision instruments and must never be used for final tensioning in torque-based methods.

Tool Power Requirements 🔧 Pneumatic impact wrenches must have adequate air supply to function correctly. Most models operate at an air pressure between 90 and 120 PSI. The required air volume (CFM) depends on the tool’s power.

Duty Level Minimum CFM (Cubic Feet per Minute) Light 4-5 Medium 5-8 Heavy 8+

Sockets and Spud Wrenches

Sockets and spud wrenches are fundamental hand tools for any bolting crew. A spud wrench features an open-end wrench on one side and a tapered spike on the other. The tapered end is essential for aligning bolt holes before bolt insertion. The wrench end allows an ironworker to bring bolts to a snug-tight condition through manual effort.

Tension Control Guns for Tension Control Bolts

While this guide focuses on hex bolts, it is useful to know about Tension Control (TC) bolts. These specialized fasteners require a proprietary electric shear wrench, or TC gun. This tool grips the nut and the splined end of the bolt, turning the nut until the spline shears off at a pre-determined torque. This provides an automatic and visual indication that proper tension has been achieved.

Following the Correct Tightening Sequence

A successful installation relies on a methodical sequence. Tightening bolts in a random order can result in uneven gasket compression, load imbalance, and gaps between plies. A proper sequence ensures uniform clamp load across the entire connection.

Achieving the Snug-Tight Condition

The first step for any pretensioned connection is achieving the snug-tight condition. This is the point where all layers of steel are in firm contact. The Research Council on Structural Connections (RCSC) defines this state with a few key indicators:

- The installer applies the full effort of a spud wrench.

- A few impacts from an impact wrench are used until the nut stops turning.

- The nut is tight enough that it cannot be removed by hand.

Bringing all bolts in a joint to this condition first ensures that the final tensioning process works to stretch the bolt, not just close gaps.

Following a Bolting Pattern (Star Pattern)

For connections with multiple bolts, installers must follow a specific sequence to ensure the load is applied evenly. A star or criss-cross pattern is the industry standard. This prevents concentrating pressure on one side of the joint. The process typically involves multiple passes.

- Pass 1: Tighten all bolts to approximately 30% of the final required torque in a star pattern.

- Pass 2: Repeat the sequence, tightening all bolts to 60% of the final torque.

- Pass 3: Repeat the sequence again to 100% of the final torque.

- Final Pass: Perform one final check on all bolts in a circular pattern to verify they are at the final torque.

- 8-Bolt Flange: 1-5-3-7-2-6-4-8

- 12-Bolt Flange: 1-7-4-10-2-8-5-11-3-9-6-12

Mastering Tightening Methods

The RCSC approves several methods for achieving the required bolt pretension. The project’s structural engineer will specify which method to use. Each one provides a reliable path to proper clamp load when performed correctly.

Turn-of-Nut Tightening Method

The Turn-of-Nut method is a simple and reliable technique that depends on bolt geometry rather than torque. After snugging the joint, the installer makes a reference mark on the nut, bolt, and steel surface. Then, the nut is rotated a specific amount relative to the bolt. This required rotation stretches the bolt into its elastic range to achieve the target tension. The amount of turn depends on the bolt’s diameter and length.

| Bolt Diameter | Bolt Length (Up to and including) | Required Nut Rotation |

|---|---|---|

| Up to 1 1/2″ | 4 diameters or 8″ | 1/3 Turn |

| Up to 1 1/2″ | Over 4 dia. or 8″ | 1/2 Turn |

| Up to 1 1/2″ | Over 8 dia. or 12″ | 2/3 Turn |

Note: These values apply when both faces are sloped not more than 1:20. For other conditions, refer to RCSC specifications.

Using a Calibrated Torque Wrench

This method involves applying a specific torque value to the nut to induce the required bolt tension. It is highly dependent on the friction between the threads and at the nut face. Because friction can vary, this method requires pre-installation verification (PIV) testing. Installers use a bolt tension calibrator (like a Skidmore-Wilhelm) to test a sample of bolts from the job lot to determine the precise torque needed to achieve the target tension. This process is essential when installing hex bolts with this technique.

Direct Tension Indicator (DTI) Method

This method uses special hardened washers with raised bumps on one face. The DTI is placed under the bolt head or nut, and as the bolt is tightened, the bumps compress. The installer uses a feeler gauge to measure the remaining gap between the DTI and the bolt head. When the bumps have flattened to a specific gap, the correct tension has been achieved. This provides a direct, visual confirmation of bolt tension.

Post-Installation Verification and Inspection

After tightening, inspectors must verify that each bolt achieves the required tension and that the connection is sound. This final quality assurance step confirms the integrity of the structure and ensures compliance with project specifications. Both technical measurements and visual checks are essential parts of this process.

Conducting Torque and Tension Inspections

Inspectors use specialized tools and procedures to confirm that the installed bolts meet the specified clamp load. These inspections provide quantitative data on the performance of the bolting assembly and the installation crew’s work.

Methods for Torque Auditing

Torque auditing is a common method for post-installation inspection. It involves checking the torque on a previously tightened fastener. An inspector performs static torque auditing by applying force with a calibrated torque wrench until the nut begins to turn again. This breakaway torque value relates to the original installation torque. Common auditing techniques include:

- On-torque method: The inspector measures the torque needed to turn the nut a small angle (2 to 10 degrees) in the tightening direction.

- Off-torque method: The inspector measures the torque required to loosen the nut.

- Marked fastener method: The inspector marks the nut and bolt, loosens it slightly, and then measures the torque needed to return the nut to its original mark.

Using a Skidmore-Wilhelm Tension Calibrator

A Skidmore-Wilhelm tension calibrator is a hydraulic load cell that directly measures the tension, or clamp load, in a bolt. Instead of inferring tension from torque, this device provides a direct reading of the clamping force. An installer places a complete bolting assembly (bolt, nut, and washer) into the device and tightens it, allowing the inspector to see the exact tension achieved.

Pre-Installation Verification (PIV) Testing

PIV testing is a mandatory procedure when using the calibrated wrench tightening method. Before work begins, the installation crew must test a sample of fasteners from the current job lot using a Skidmore-Wilhelm calibrator. This test verifies the performance of the bolting assembly and determines the specific installation torque required to achieve the necessary pretension for that batch of bolts, nuts, and lubricant.

Performing Final Visual Checks

A final visual inspection is a fast and effective way to spot potential issues. According to AISC and RCSC guidelines, every bolted connection requires a visual check. This ensures all components are correctly installed and seated.

Inspecting for Proper Stick-Through

Inspectors visually confirm that the bolt length is correct. A properly installed bolt will have adequate thread engagement, typically indicated by the bolt end protruding at least two full threads past the outer face of the nut. This is known as proper “stick-through.”

Checking for Gaps or Misalignment

A visual check ensures that the steel plies are in firm, solid contact. There should be no visible gaps between the connected surfaces. Any gaps indicate that the snugging process was incomplete and the connection did not achieve full clamping force.

Verifying Washer and Nut Orientation

Inspectors verify that all hardware is correctly placed. This includes checking that hardened F436 washers are used under the turned element (usually the nut). For sloped surfaces, they confirm that beveled washers are correctly oriented to provide a parallel bearing surface.

Marking Bolts After Final Tightening

Marking a bolt after final tensioning is a common practice. An inspector or installer uses a paint marker to draw a line from the bolt tip across the nut and onto the steel surface. This mark provides a clear visual confirmation that the bolt has been tightened and inspected, which is especially useful for verifying the Turn-of-Nut method.

Common Mistakes When Installing Hex Bolts

Even with the right components, installation errors can compromise a structural connection. Installers must recognize and avoid common pitfalls to ensure safety and performance. These mistakes often relate to improper tightening, thread damage, and procedural shortcuts.

Avoiding Improper Tightening

Achieving the correct bolt tension is a balancing act. Both too little and too much torque create significant risks for the connection’s integrity.

Risks of Under-tightening and Insufficient Clamp Load

An under-tightened bolt fails to create the necessary clamping force. This insufficient pressure leaves the joint vulnerable to failure.

- Vibrational Loosening: Lateral forces from vibration can overcome the low friction in the joint. This causes micro-slip, allowing the nut to rotate and eventually walk off the bolt.

- Fatigue Failure: Insufficient clamp load allows the connected parts to move, subjecting the bolt to repeated stress cycles that can lead to fatigue failure.

Dangers of Over-tightening and Bolt Yielding

Applying excessive torque pushes a bolt beyond its elastic limit, causing permanent damage. This is known as yielding.

- Bolt Breakage: The tensile stress from over-tightening can exceed the material’s strength. The bolt stretches too far, thins out (necks), and snaps.

- Thread Failure: Extreme torque can strip the threads on the bolt or nut. This failure mode is difficult to detect during installation and leaves a weakened fastener in service.

Preventing Thread Damage

Protecting the threads is essential for proper nut engagement and achieving the target tension. Galling and cross-threading are two common forms of thread damage.

What is Thread Galling and How to Prevent It

Thread galling is a form of cold-welding that occurs when pressure and friction cause threads to seize. It is most common with certain metals.

| Metal Type | Galling Risk | Primary Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium | Very High | Surface Reactivity |

| 316 SS | High | Oxide Layer Breakdown |

| Aluminum | High | Material Softness |

Installers can prevent galling by slowing down installation speed to reduce heat, applying an approved anti-seize lubricant, and ensuring threads are clean.

How to Avoid Cross-Threading

Cross-threading happens when a bolt and nut are misaligned during initial engagement. Forcing the connection damages the threads and prevents proper tightening. The best prevention is simple: installers should always start threading a nut by hand for several turns before using any tools.

Other Critical Installation Errors

Procedural shortcuts and ignorance of material properties introduce serious risks. Following established protocols is non-negotiable.

The Dangers of Reusing High-Strength Bolts

High-strength structural bolts are designed for single use. The RCSC specification is clear on this point.

“ASTM A490 bolts and galvanized ASTM A325 bolts shall not be reused…Pretensioned installation involves the inelastic elongation of the portion of the threaded length…[they] are not consistently ductile enough to undergo a second pretensioned installation.”

When tensioned, these bolts stretch permanently. Reusing them risks fracture because they have already lost the ductility needed for a second safe installation.

Using an Impact Wrench for Final Torque

An impact wrench is a powerful tool for snugging bolts quickly. However, it is not a precision instrument. Installers must never use an impact wrench for final tensioning with torque-based methods. Its inconsistent output makes it impossible to apply a specific, final torque value accurately.

Ignoring Surface Preparation Requirements

Clean and flat connection surfaces are fundamental to a strong joint. Debris, rust, or mill scale on the faying surfaces prevents the steel plies from achieving firm contact. This debris absorbs clamping force, leading to a falsely high torque reading and an under-tightened, unsafe connection.

The integrity of any structure depends on the correct selection, installation, and inspection of every single hex bolt. Mastering the fundamentals—from choosing the right grade and preparing surfaces to applying precise torque—is essential for safety and compliance.

Historical failures, like the Hyatt Regency walkway collapse, underscore the catastrophic results of improper fastener design. Even simple errors, such as under-torquing, can lead to fatigue failure in critical components.

Consistently following these best practices and avoiding common pitfalls ensures that all bolted connections are strong, durable, and secure.

FAQ

Can installers reuse high-strength bolts?

No. High-strength bolts like ASTM A325 and A490 are designed for single use. The initial tightening process causes permanent stretching (inelastic elongation). Reusing them creates a significant risk of fracture under load, as they have lost their original ductility and strength.

What does “snug-tight” mean?

Snug-tight is the point where all steel layers are in firm contact. An installer achieves this using the full effort of a spud wrench or a few impacts from an impact wrench. This step ensures final tensioning stretches the bolt, not just closes gaps.

Why is bolt lubrication so important?

Lubrication reduces friction between the threads and the nut face. This ensures the applied torque consistently translates into the correct bolt tension (clamp load). Unpredictable friction can lead to dangerously under-tightened or over-tightened connections. Using unspecified lubricants is a critical error.

What happens if I use the wrong grade of nut?

Using a lower-grade nut with a high-strength bolt is extremely dangerous. The nut’s threads can strip during tightening before the bolt reaches its required tension. This results in a failed connection. Always use a nut with a grade compatible with the bolt.

Can I use an impact wrench for final tightening?

No. 🔧 An impact wrench is excellent for bringing a joint to the snug-tight condition. However, it is not a precision tool. Installers must never use it for final tensioning, as it cannot apply a specific, calibrated torque value accurately.

What is the “two-thread” protrusion rule?

This rule ensures full nut engagement. A properly installed bolt must extend at least two full threads beyond the outer face of the nut. This visual check confirms the bolt is long enough to achieve its full load-carrying capacity.

Why must I clean the connection surfaces?

Clean surfaces are essential for achieving the correct clamp load. Debris, rust, or mill scale can absorb the tightening force. This leads to a false torque reading and an under-tightened joint, which compromises the connection’s structural integrity and safety.